攻殻機動隊 M.M.A. - Messed Mesh Ambitions_

Ressurectionlands.com, 2020, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

Inheritance of Memory and Plurality of the Future

Interviewer: Naoya FujitaLayout: Shota Seshimo

Illustrations: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley

Inheritance of Memory and Plurality of the Future

Here we present a discussion between artist Ginga Kondo, philosopher Reina Saijo, and media researcher Tomoko Shimizu. The conversation between the three begins with Motoko Kusanagi’s unstable identity, and proceeds to an analysis of representations of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), cyborgs, and robots. The discussion they hold while going back and forth between the work and reality also opens up the possibilities of the Ghost in the Shell series. The series has been described as an eclectic, deconstructive hybrid with motifs associated with techno-Orientalism seen in depictions of the cyber worlds and cities, on a foundation of Donna Haraway’s cyborg feminism. Through this reinterpretation, our bodies, society, and technology will also take on different appearances.

Kondo uses various media such as VR, AR, and games to create works of art that explore the relationship between lesbianism and art, and actively communicates her thoughts as a wheelchair user with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS) – an incurable disease – and as a sexual minority. With a background in analytical philosophy, Saijo studies feminist philosophy and the ethics of robotics. In particular, she has attracted attention for analyzing robots’ social positioning and ethical concerns from the perspectives of gender and sexuality. Shimizu specializes in cultural and media theory, and is intimately familiar with Haraway’s theory. She has a critical perspective on power relations in global society, and is known for her bold criticism of contemporary art and subcultures.

As they analyze technology through intersecting perspectives including gender, ethnicity, and class, the topic eventually turns to the future of pluralism with AI. Can we liberate technology from the majority and achieve openness toward serendipity and plurality? Envision AI taking on the local context and passing on the memories of the community. In this interview, we explore the potential of these sorts of alternative AI.

目次

Motoko Kusanagi’s sexuality

KondoFor this roundtable discussion, I revisited director Mamoru Oshii’s films “Ghost in the Shell” and “Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence,” which I’ve watched many times since I was in elementary school. I was really struck by the way Motoko Kusanagi has an unstable sense of her own sense of self and identity. “Do I exist?” “I’ve never seen my own brain, so I don’t know if I’m really human.” That’s the sort of doubt she struggles with. She uses a mass-produced prosthetic body, and identical faces to hers can be seen all over the city. Her body is both human and a commodity, which reminds me of the homogenization and commodification of the female gender.

SaijoI also first encountered the Ghost in the Shell series through the movie version directed by Oshii. Of course, I’m interested in Motoko’s questions regarding her personal identity, too. Even after Batou tells her, “Everyone treats you like a human, and your brain is human, so who you are is yourself,” she is unable to stabilize her own identity. Arguments that seek the basis of personal identity in relationships with others are common in the modern day, but hers is different. I found it intriguing that the issue was not about how others treat her, but how she feels about herself. As Kondo points out, this anxiety is also related to Motoko’s body as a minority.

ShimizuThat’s right. Along with Motoko’s questioning, I thought the concept of a “ghost” was fascinating. As mentioned in your book, Fujita, the term originates from Arthur Koestler’s book “The Ghost in the Machine.” In Ghost in the Shell, ghosts are deeply connected to souls and personalities, and are also connected to networks and open to others. It is hard to say there’s a physiological basis for that, and it’s laden with extremely ambiguous images. It’s as if we stand between existence and non-existence, wandering between human and machine, information and life. The director himself – Oshii – called “Innocence” (the seqel to Ghost in the Shell) “a story of non-existence.”

SaijoIf we trace the origins of “The Ghost in the Machine” further back, we come to Gilbert Ryle’s “The Concept of Mind.” This book was heavily influenced by 20th century behavioral psychology. The argument has been made that all mental terms refer to actions and behaviors taken in the external environment, and that it’s philosophical nonsense to assume that there is an independent mind other than that. That means an introspective mind (the ghost) does not exist separate from the body (the machine). In other words, ghosts should have been erased from the outset. In Oshii’s works, they’re depicted as something positive, and something that should exist. In terms of philosophical history, behaviorism draws more and more criticism the more time goes by. However, the mechanism by which and specific evolutionary stage at which consciousness and the mind arose are not clear. We still don’t know where the ghost is located.

The merging of Motoko with the Puppet Master is depicted both in the original work and in Oshii’s film version. I think this is both a metaphor for marriage and a metaphor for reproduction. I think a certain sort of sexuality is expressed in the form of bonding with AI and artificial life forms. What do you think about that point?

SaijoI think that the merging of the Puppet Master and Motoko is depicted with a different structure from reproduction. If it were sexual reproduction, a new individual would be born from two individuals, but that doesn’t happen in the story. However, it is interesting that Motoko herself undergoes some sort of transformation through this process. Normally, individuals do not change when they are bonded by marriage, but Motoko’s personality expands. Since we’re discussing the topic of marriage, I would like to add a little more. The views on gender in the original work are extremely conservative. There is a clear division between masculine and feminine bodies, and we aren’t shown many ways to overcome that binary system.

ShimizuThe setting is certainly futuristic, but I feel the portrayal of gender doesn’t break away from stereotypes. However, I think Motoko is a little more complicated than characters in other works that have cyborgs, AI, and androids as their themes. In Shirow Masamune’s manga version of Ghost in the Shell, Motoko is pansexual or lesbian. On the other hand, I felt that there wasn’t much expression of sexuality in Oshii’s film version

KondoGenerally speaking, Motoko’s sexuality isn’t really portrayed in Oshii’s version. “Ghost in the Shell 2.0” was released around the same time as “The Sky Crawlers,” and it’s a bit different. It was created by replacing some of the original Ghost in the Shell footage with computer graphics and re-editing the sound effects, but there’s one major change. The voice of the Puppet Master was changed from a voice actor named Iemasa Kayumi to a voice actress named Yoshiko Sakakibara. Along with this, the third person pronoun used by the Programmer, the creator of the Puppet Master, was also changed from “he” to “she.” I think this emphasizes Motoko’s sexuality. The original work emphasized the gender-crossing image of a male voice actor’s voice in a feminine body. Here, the homosexual aspect is emphasized more. I think it’s interesting that making such variations in each work creates an overarching “Ghost in the Shell” whole, while maintaining both meanings.

What we can say about the work as a whole is that Motoko treats her own body not as a sexual thing, but as an object. However, Batou sometimes averts his eyes from Motoko’s body or lets her put on his jacket when he sees her unconcerned with her form. In other words, he views Motoko’s body based on heterosexual norms. At the beginning of the original work, there is a very famous preface, saying “In the near future – corporate networks reach out to the stars. Electrons and light flow throughout the universe. The advance of computerisation, however, has not yet wiped out nations and ethnic groups.” I wonder if this is also a near future where computerisation has not become so ubiquitous that gender will disappear.

Cyborgs and sick bodies

The Ghost in the Shell series is often discussed in terms of its relationship to Donna Haraway’s cyborg feminism. What are your thoughts on that front?

KondoThere’s even a character in “Innocence” named Haraway, just like that. (Laughter) However, with regard to Haraway, I think it makes more sense to read it from a companion species perspective, rather than the cyborg theory. As you know, Oshii is very particular about depicting dogs.

ShimizuHaraway is indifferent to posthumanism. She refers to the cyborg as a being where the literal and the figurative are always working in an ambiguous manner, and which is feminine and female in a very complex way. The cyborg is also a thorough materialization of the social-technical relations formed through the implosion of information technology and biotechnology after World War II. Haraway therefore sees potential in methods that think of all of us, whether humans, animals, plants, or machines, as a single communication system. I think this is also the origin of a focus on hummus and compost, as well as dogs, which are companion species for humans. This is not a bond or structure based on family or blood ties, but rather a non-familial unconscious relationship that is not picked up in the story of the Oedipus complex. This unique ontology focuses not on intimacy through love, but on intimacy through friendship, work, play, and connections with non-human things.

I think the Ghost in the Shell series is connected to this worldview in its depiction of the cyber world. But on the other hand, as was mentioned earlier about gender, there are some aspects that aren’t easy to shed in the setting. I think the feeling of not being able to escape from humanity really resonates with our reality.

If we step away from the work and turn back to reality, we are all starting to gain access to technology that allows us to become anything we want, whether it’s a beautiful girl or an animal, in a space like the metaverse. While we have not yet become cyborgs, we may soon be able to control our own bodies as we wish. I think there certainly is a desire at present to have our natural bodies be free and subject only to our own wills, in that regard. What would you say on all of that?

ShimizuIn terms of technology and the body, I found many hints from “Becoming a Cyborg: Technology, Disability, and Our Imperfections” co-authored by Kim Cho-yeop, a Korean science fiction writer who is also disabled, and Kim Won-young, a lawyer and performer. Instead of using technology to seek the perfect body, and treatmeant toward that end, people are now considering technologies to enable people with disabilities to live rich lives with their disabilities as they are.

KondoKim Cho-yeop also published a piece called “Mari’s Dance” in the October 2023 issue of SF Magazine. It’s a story about people born with disabilities, who use the technology they created to change the world. There are technologies that take advantage of the traits of each disorder, and the story eventually comes to include terrorist attacks. The relationship between technology and disability is depicted in a different way from the so-called treatment model.

In contrast to the treatment model, the social model of disability – which people have been discussing a lot recently – separates disability (social deficiency) from impairment (organic deficiency), and there is a movement to change society with a focus on the former. However, I wonder if that’s really enough. I have a disease called myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and usually use a wheelchair. Not being able to climb stairs in a wheelchair is definitely a disability, and it always gets in my way. On the other hand, I’ve always been concerned about the somatic sensations that arise from impairment due to illness. In fact, the social model of disability has been criticized by feminists for ignoring experienced sensations.

I think the same can be said for cyborgs. If I were to become a cyborg, it would give rise to issues of some sort or another. And when it did, how would that sensation be perceived, and how would it be treated in society? I focus on the anxiety of identity portrayed in Ghost in the Shell because it seems to place importance on such experiences and sensations.

ShimizuEven in the Ghost in the Shell series, cyborgs are not depicted as perfect bodies; instead, they’re bodies that constantly require maintenance and care. On the other hand, the characters also seem to be obsessed with the “ideal” and “healthy” bodies of human society. It also stood out to me that Batou lifts weights.

KondoThat’s right. I’d like to compare it with some other works. In “Queer Cinema Studies,” Makiko Iseri discusses Mad Max: Fury Road. The story features a female character named Furiosa, who is missing one hand and has it replaced with a prosthetic arm, as well as an enemy character, Immortan Joe, who also has a diseased body and uses a respirator. Iseri’s analysis states that while the prosthetic arm that compensates for a disability is depicted as heroic, the diseased body itself is depicted as villainous.

On the other hand, for example, the hacker Kim in “Innocence” deliberately uses his diseased body as a prosthetic body. This is interesting as a case under cyborg theory. I think Mamoru Oshii has become more conscious about his own body and illness since “Innocence.” For example, the pilot video “G2.5” was produced around the same time as “Ghost in the Shell 2.0,” which came up earlier. The G2.5 video is included as a bonus on the Blu-ray disc of “Garm Wars: The Last Druid,” and depicts women who appear to be Motoko naked and fighting each other, with their bodies gradually disintegrating. I’m really curious about what would have happened if this had been made into a movie.

Desire for enhancement

SaijoHowever, if you were to ask me whether cyborgs in Ghost in the Shell were created with the aim of filling in deficiencies or imitating a “healthy” body, I don’t think that’s the case. In the context of ethics, I think the cyborgs are aimed at increasing physical or mental ability, or in other words, enhancement, rather than treatment. When it comes to enhancement, I mainly refer to the work of ethicist Takeshi Sato, but perhaps it’s easier to imagine doping in sports, for example. In the latter half of the 20th century, enhancement debates centered on the use of antidepressants to make people more sociable, and the pros and cons of smart drugs to improve concentration. While it’s not easy to separate this from treatment, and can be hazy, it may also apply to things like cosmetic surgery. There is also the idea of moral enhancement to create more moral actions and judgments and better human beings, as advocated by the ethicist Julian Savulescu.

ShimizuYes, that’s right. You could say it depicts the imagination of transhumans with powers that surpass those of humans. “Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex” features a character who was born with a weak body, and whose parents forbid him from having a prosthetic body for religious reasons. After the character dies, his brain is connected to the AI of a tank and commits a terrorist attack, then his brain is eventually fried. There’s a memorable scene in which Motoko says that when his brain was fried, she felt a strange emotion that wasn’t pride or revenge. As if he was saying “Well mom, what do you think of my new steel body?” It left an impression on me as an episode that expresses the connection between the longing for a strong body and having a prosthetic body.

KondoI spoke about “Mad Max: Fury Road” earlier, but when representations of disabilities appear in science fiction works, they’re often portrayed as superpowers. Motoko has a past where she was seriously injured in a plane crash and became a cyborg in order to overcome it. Here, overcoming illness and acquiring a superhuman body overlap. Even in the real-life London Olympics (2012), there was a story about people with disabilities who were more than human. Even in the field of disability, I think the pressure to enhance and become transhuman is extremely strong.

SaijoAs for the practical issue of enhancement, unlike medical treatment, the problem is that it will be made a privilege by the wealthy as a “luxury” or “elective item.”

KondoI think you’re right. I don’t believe in promises and propaganda saying that the advance of cyborg technology will bring about a free world. I think there is simply no basis for that. New technology like the Metaverse costs a lot of money if you want to buy a high-precision avatar. And if you want to run it, you need a PC with high specs. This is ultimately a phenomenon under capitalism, but if we envision cyborg technology with universal access, then you end up unfair in the same way as the actual world right now.

SaijoEven if enhancement could overcome ethical issues in the technology and become widespread enough for everyone to use, there would still be challenges. What would happen if doping became the norm, and you would no longer be able to win or be eligible to participate unless you were doping? In that case, autonomous decisions become almost impossible. There’s no issue with anyone at all accessing a VR avatar so long as the creator retains it as well, but more physically or mentally invasive technologies aren’t simply improved by democratization.

The way technology magnifies inequalities is a global issue. I’m also interested in the discussion of autonomous decision-making that Saijo pointed out. For example, if we were to be able to manipulate our own brains, where would we find the will and agency to decide whether or not to do so? The concept of the ghost depicted in the story may be intended as the virtual decision-making center.

ShimizuIn the Ghost in the Shell anime series, the word “bug” is sometimes used in relation to the prosthetic bodies of Motoko and her teammates. The people of Public Security Section 9 are under the control of the state, and their bodies are treated as weapons. So if the prosthetic body doesn’t function well as a tool in battle, if there’s a bug in the prosthetic body that cannot be fixed, then it will be destroyed. As a result, Motoko and her teammates’ abilities to act based on their sense of justice are restricted, their past memories are erased, and they are no longer able to choose how their bodies should behave.

I think Haraway’s cyborg body was a rather positive portrayal of how it connects with different things as a communication system. In contrast, in the Ghost in the Shell series, when people share a body or brain, their memories can be rewritten or hacked. They may even have their will, independence, and ghost stripped away by powerful institutions – the state. In this sense, questions of technology and democracy are likely to become increasingly important issues in the future.

Changing views of life and death?

Last year, I saw an exhibition called “The END Exhibition.” The content was very interesting, because it questioned views on life and death through technology. We can already create agents based on our life logs that have the similar bodies and speak in the same way as when we were alive. In such an era, how will the relationship between information and life change, and how will ethical views regarding death change?

SaijoDoes that mean you can create a bot and have a conversation with a family member or someone close to you even after they have passed away? I’m somewhat skeptical about whether this will bring a change in ethical views. That’s because when a person dies, it means that they lose not only their physical body but also their social personality. To put it simply, the assets you had will of course disappear, and the reactions and interests of those around you will change from when you were alive. So even if an AI that has a body similar to the deceased person and is capable of communication, we’ll probably interact with it as a separate agent from the original person. Alternately, I don’t think there will be many people who would be more willing to die just because they could use that sort of AI agent.

When I read books by Americans about whole brain scanning, they say that if you could scan all of your data and create a copy, it would be the same as the original person. I think this is based on the idea that life is information and consciousness is produced by brain systems. But personally, I feel that once my body dies, that will be the end; even if something lives on as information, it will not be me. I wonder if this view of life and death is influenced by the culture of each country or region.

SaijoI can understand it as sort of a thought experiment. It might be similar to the famous argument developed by the philosopher Derek Parfit in his book “Reasons and Persons.” It’s based on the idea that when memories are stored safely and downloaded to another body, the person can continue to exist perfectly, too. If this were actually possible, I’m sure some people would try it. In Parfit’s argument, if there is an accident in which the memory of the original body remains unerased due to an operational error, and there are two bodies with the same memories split into two, which one is the real person?

KondoI think your question about whether technology changes our view of life and death is very difficult, Fujita. That’s because it seems to be asking the person’s current view of life and death, here. If a new technology were to appear, how would you feel then? People who say they don’t care if they die so long as they can upload themselves probably thought that way from the beginning. When imagining the future, I think we must also think about the present moment as we do so.

SaijoHowever, it’s not uncommon for decisions regarding life and death to change due to technology. There are even people who want to die before they become a burden to other people, so they want euthanasia to be legalized. However, when these technologies and systems become reality, it isn’t clear whether people will calmly and coherently advocate the same decision in the face of death.

ShimizuSpeaking of technology and views on life and death, I was reminded of a project called “Democratizing Death” being undertaken by a research team at Columbia University called DeathLAB. In Japan, curator Yosuke Takahashi planned an exhibition at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. At the time of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, there was a huge controversy over how to mourn 3,000 people of different religions and races. Taking this as an opportunity, DeathLAB is working on how to deal with various issues surrounding death in large cities, such as a lack of cemeteries, a declining birthrate and aging population, and carbon dioxide emissions from cremation. Specifically, they set up a memorial site on the Manhattan Bridge in New York, with the idea to hang a methane-producing coffin under the bridge, which will glow with the energy obtained from the decomposition of the body by bacteria. This project was conceived in the context of the lack of space for burials in cities and the heavy environmental impact of cremation. It is a bold concept differing from the traditional view of life and death, as it doesn’t separate the dead from the city, but instead allows the dead to be mourned in the middle of the city while being recycled as public facilities and infrastructure.

BCL, formed by artists Shiho Fukuhara and Georg Tremmel, has a work called “Biopresence” that preserves the genes of the deceased in the genes of trees. It’s what you might call a “living grave marker.” I think both cases show interesting approaches for thinking about our views on life and death and the conflicts that arise at the stage of death, when our bodies are lost.

Methods of resistance

KondoShimizu mentioned earlier that in the Ghost in the Shell series, the body of a cyborg is owned by the state and used as a weapon. Even their memories that serve as a place of refuge are controlled by the government, and when a person is discharged from the military, their identity may be erased as well. Although this is only a fictional story, I also believe that it is a story of a reality that we should resist.

An interview with Ramona Jingru Wang was recently published; she’s an Asian artist active in the United States. She criticizes Orientalism in cyberpunk, and creates works that turn it on its head. In an interview, she said, “I took advantage of the cyborg appearance and expressed it as both organic and mechanical, reinterpreting it as something that celebrates the fact that we are hybrid beings.”

The Ghost in the Shell series also has this aspect of Orientalism. In Oshii’s film version, Orientalism is incorporated and goes through complex refraction by taking the perspective looking from the West toward Japan and turning it back toward Hong Kong and China. It is also a work that reproduces power structures within Asia. This may be true of all works in the cyberpunk trend.

ShimizuRegarding the Western-centric and androcentric technology at the root of Orientalism, I think we need to think about who/what is being excluded, why, and how. Yuk Hui, a philosopher from Hong Kong, proposes the concept of technodiversity. When he discusses technology in the West, he always starts with Greek myths like Prometheus and Epimetheus, and goes on and on about Europe. He says that the meaning of technology is not unique to Western culture, but has been experienced and described differently everywhere, such as in Japan, China, and Latin America. Through the concept of technodiversity, Yuk is argues for the need to redraw the history of technology as multiple histories.

This is a different argument from the one in Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism.” Humans are always at the center of discussion of Orientalism, and it is tied to various issues of multiculturalism. However, Yuk works to reconsider the world from the perspective of multi-naturalism – proposed by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro – which states that one culture is based on many forms of nature. For technology, there is no universal technique. Rather, there are various techniques depending on the local context.

This is not a mere theory on paper. For example, Ai Hasegawa, who is active as a speculative artist, has a work called “(Im)possible Baby.” Based on the genetic information of Asako Makimura and Moriga, who entered into a same-sex marriage at PACS in France, she created a family photo of a hypothetical child that could be born from their genetic information. Her work turns a critical perspective on a society that adheres to monogamy and kinship, and simultaneously questions the ethics of biotechnology for creating children between same-sex couples. It shows the diversity of values regarding reproduction and bioethics, and a complexity that is difficult to simplify down. If technology is changing the way we live, then I think it is necessary to discuss its value and how to utilize it, asking what kind of society we should aim for together with science and technology, and what vector we should use this technology toward.

I also think that the movie After Yang, directed by Korean-American Kogonada, resonates with what Kondo said. In the film, Yang, a carefully programmed AI humanoid robot with an Asian appearance, acts as a babysitter and older brother to an adopted Chinese daughter. The robot breaks down, but when robots are depicted as Asians, women, or children, I think they are often engaged in care work or become objects of romance. On the other hand, when robots are portrayed as white men, I feel like they often try to dominate the world or bring about catastrophe, as seen in the movie Transcendence. The representation of robots and AI is completely different depending on ethnicity and gender. I think this situation can also be analyzed from the concept of technological diversity.

KondoIn a similar case, an Australian artist called VNS Matrix created a game featuring a feminist group and criticized androcentrism. Here, we can also see the direction of incorporating media that is strongly connected to pop culture, highlighting existing images and the norms hidden therein, and internally criticizing and resisting them.

A sort of DIY culture is celebrated in these creative practices. In Paul B. Preciado’s “Countersexual Manifesto,” he talks about how creating dildos with 3D printers allows people to act freely. I also think DIY is important for resistance, but to what extent should we actually do it on our own? As an artist who creates works using 3D computer graphics and games, I’ve always been worried about this. It’s especially difficult to work with platforms. For example, the game engine Unity promised to democratize games, but suddenly changed its pricing structure, leading to fierce opposition from individual developers. Platforms controlled by large companies are subject to sudden policy changes. In order to get your work seen, you may have to use Instagram and X (formerly Twitter), regardless of whether you agree with the idea of them or not. When it comes to works that use technology, there are limits to what can be done on an individual scale.

ShimizuI think you’re exactly right. Shawanda Corbett, an artist who has

African-American roots and a physical disability, is one of the artists who confronts these issues. She calls herself a “cyborg artist” and incorporates the results of her graduate school AI research into her works. She also said that it is difficult to utilize technology alone, and that the community she lives in is like her own body.

AI and gender representation

We talked about Said earlier. In “Orientalism,” he points out the problem that subordinate and dominated subjects are often represented as women. I think that “Ghost in the Shell” also exists in the context of using or rewriting “techno-orientalism,” and there is an Orientalist composition in the representation of AI as well. For example, the journal of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence was criticized for using an illustration on its cover of a female android cleaning with a broom. However, there is also a debate about East and West, and in Japan, where character culture is influential, it’s easy to imagine that only representations of young women will used, as is already the case. As AI becomes commonplace in society, how should we think about gender representation in AI?

SaijoFirst of all, I’m quite wary of comparing the West and the East. Japan is friendly with robots, but in the West they are considered hostile, and Shinto and Buddhism are involved… I can’t judge whether a theory on Japan’s special status corresponds with the facts. Besides, it’s difficult to find something attractive from an ideological or academic point of view in such a discourse. If that was the case, what about C-3PO and R2-D2 from Star Wars? (Laughter) It’s impossible to prove or disprove the claim that Astro Boy and Doraemon reflect Japanese religious views, and it may simply be that Osamu Tezuka and Fujiko F. Fujio were very skilled at character design. Recently, a philosopher named Makoto Kureha addressed this exact issue in his paper “Japanese People and Robots: A Critique of Techno-Animism.” Also, Said’s “Orientalism” is basically focused on the Middle East and does not include much of East Asia. If we simply talk about the West versus the East, I feel that there’s a risk of erasing the diverse cultural areas included in the “East.”

Of course, this isn’t just an issue in Japan. While it’s far from everyone, I sometimes get tired of Western researchers expecting me to have an Oriental view of robots. It’s like the European art world at the beginning of the 20th century, othering traditional African art and finding something “new” about it. It’s true that each community has its own unique needs, and I think the honest approach is to conduct research on an empirical basis.

Going back to the question from Fujita, why is AI gendered in the first place? When humans see entities using natural language, for some reason they tend to anthropomorphize them. Assistant software like Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa are also shrouded in female gender representations. The latter in particular was criticized by UNESCO in 2019 as a harmful example that exacerbates the gender gap. First of all, unnecessary gendering should be avoided.

But gendering may be necessary for some products to satisfy certain needs. For example, sex robots. I once saw a product image with a transparent head on the website of an American company that manufactures and develops AI-equipped sex robots. I think design clearly showing “it’s a machine, not a human” is desirable because of honesty. On the other hand, companies also need to make users feel attached to their products, so they need to find a balance in how far they can push their human image to the forefront.

As a separate issue, I would like to mention that it’s extremely difficult to de-gender voices. People seem to have a strong tendency to distinguish whether someone is male or female based on the tone of their voice. There is also a group in Europe that is developing a “genderless voice” called “Q.” Please give it a try and see what you think. When I asked students in class, many of them responded saying that it sounded like a young man. Serena Sutton’s paper “Gender Ambiguous, not Genderless” says it is more appropriate to describe “Q” as having gender- ambiguous rather than being “genderless,” and has criticized it as contributing to stereotypes about non-binary people.

ShimizuThe issue of voices is interesting. Voice comes from the body, but it is not a part of the body, and it supports language without belonging to it. The issue of technology and voice is also related to what Kondo said earlier, about how the voice of the Puppet Master varies from work to work, making up the whole story of Ghost in the Shell together.

SaijoAs for the relationship between character culture and technology, which Fujita asked about, I think that could be another discussion. If we consider the case of sex robots, we should design them in a way that causes as little harm as possible, just as we do with pornography. For example, should we be critical of robots that reflect racial fetishism?

This is an important point of discussion, but considering that robots are man-made objects, I don’t think it will be easy to solve. I mentioned the point of distinguishing AI from humans. That’s because some people feel sexual or romantic attraction toward AI, robots, characters, and other artificial objects. Especially in Japanese otaku culture, there are many people who love characters and consider them irreplaceable. These artifacts are never a substitute for human counterparts but unique and intimate objects. It’s unfair that just because a character design represents certain stereotypes of real women or men, people who love it are immediately criticized for being complicit in discrimination. Isn’t that the same as a one-sided argument that married couples, consisting of a man and a woman, should divorce because they endorse patriarchal gender views?

Technology and inheritance of memory

KondoCan we talk a little more about the relationship between technology and representation? When the live-action version of Ghost in the Shell was released, there was criticism that Motoko had been whitewashed. What really impressed me as I watched the discussion was how important Motoko is to Asian Americans, including Japanese Americans. Her presence was very important to people who had difficulty expressing themselves.

I think that kind of discussion is important. It means thinking about the present as an accumulation of local memories. Unique histories and contexts are not necessarily local. For example, if you are queer, you have some local parts and some global parts. Afrofuturism – which is often referred to regarding the relationship between sci-fi imagination and ethnicity – is sometimes shunned because the subjects producing the discourse are not necessarily African. The reason for this is that it is thought that it may lead to concealment of the legacy of memories of African people who immigrated to the United States, and those who were brought in through slavery.

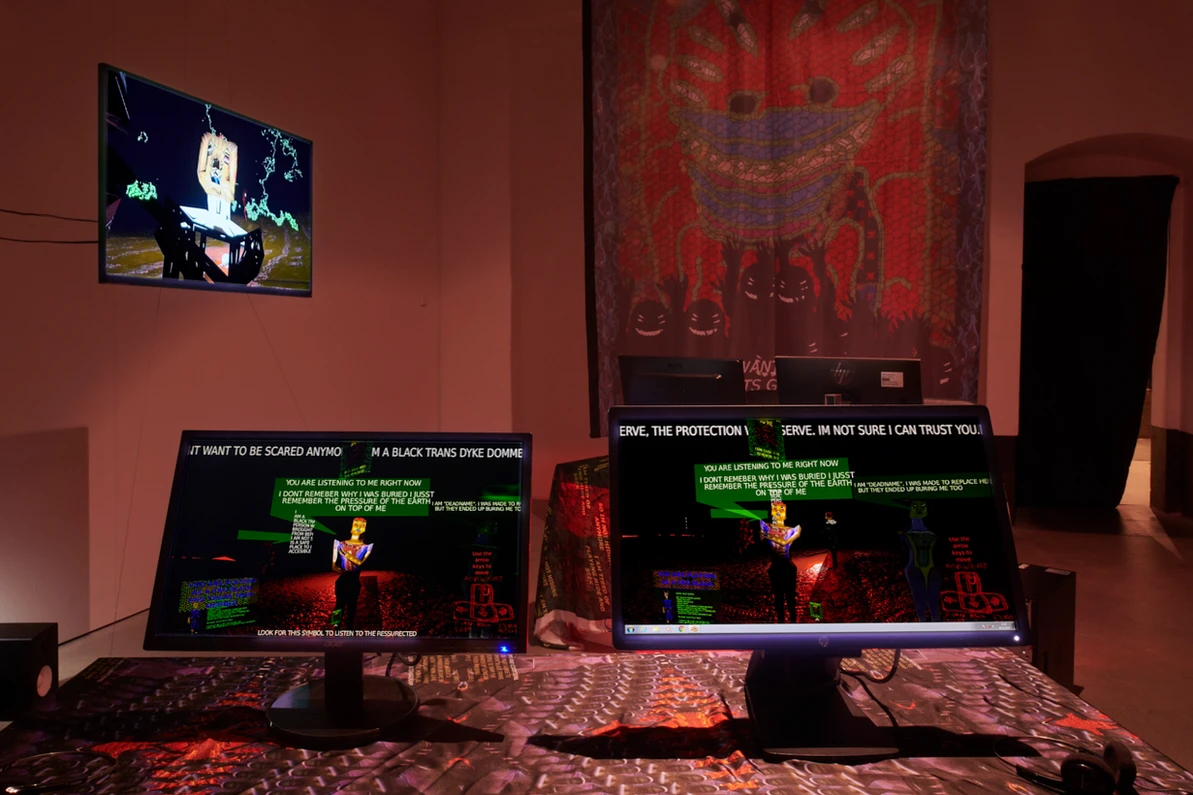

In this context, I would like to introduce the artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. She is an American black trans writer whose work touches on the black trans experience through game-like experiences. A slightly nostalgic atmosphere is also important, as it allows us to think about the past. I think the theme of passing on intersectional history through technology is woven into this.

Shimizu

When it comes to passing on memory through technology, I think the Sydney Jewish Museum is also doing some interesting work. Recently, American Studies researcher Yujin Yaguchi addressed this issue in a paper titled “AI and Historical Testimony in History Museums.” At this museum, Holocaust survivors volunteer to talk about their experiences, but as the population ages, some find it difficult to speak. Therefore, they are working on a project called “Dimensions in Testimony,” which uses AI technology to allow visitors to have conversations with survivors even after they have passed away, and record their testimonies so that their memories can be passed on. In addition to the audio, images of the survivors are projected onto screens, making it seem as if they are speaking to you. By doing this, they hope to create AI that can answer any questions future museum visitors might have. However, whether the person asking the question is a child or an adult, the way the AI responds, the content, and their facial expressions don’t change at all, and it isn’t possible to have an interactive discussion. So it doesn’t seem to work as well as dialogue between humans. One of their ideas is to use AI as an agent that connects individual experiences and memories to history as a public memory.

SaijoI also thought that was a positive example. After obtaining permission from the parties involved, it’s clearly stated whose testimony is being used for study, and it’s designed to ensure that visitors don’t mistake it for the original person. An example of the opposite would be to use AI to resurrect singer Hibari Misora and have a replica that looks exactly like her singing songs. Of course, they didn’t have her permission, and they falsely pretended that they were resurrecting her.

ShimizuWhat Saijo said reminded of the Korean artist Kim Jung Gi. Less than three days after his death, a former French game developer released a tool to generate images in Kim’s style, and received severe criticism and backlash. Along with comments calling it a “tasteless publicity stunt” and “discrimination against Asians,” there were also comments asking why artists should be forced to work even after their deaths.

This makes it into a kind of labor problem in which a person is forced to continue producing “works of art” even after their death, regardless of their wishes. In recent cases, Hollywood actors and screenwriters have gone on strike against the use of AI and to demand fairer distribution of profits better working conditions.

SaijoEven in the case that Shimizu mentioned, I think ensuring ethical and fair procedure is essential. The Jewish Museum example mentioned earlier takes this point seriously and has designed an experience where visitors can come into contact with real testimonies through an interactive interface. I think that’s a very good attempt at this. Even if it is a human and not an AI, their memories are rewritten and retold every time they remember something.

Towards future plurality

Through the dialogue so far, I think we’ve come to a vision of a pluralistic future while carrying on each of our local cultures and personal uniqueness. Finally, could you tell us your thoughts on what technology should be like in the future, taking into account its historical nature?

SaijoThe philosophical methods that I’ve learned as specialized knowledge are far from historical. So I am unsure if I can give a good answer, but I would like to think about technology from an ethical perspective. When thinking about the future of technology, I think we can’t ignore the large-scale impact it will have on future generations and the global environment. Radioactive waste has an impact that lasts hundreds of millions of years. Even problems that aren’t that big, like asbestos – which is now banned – still exists and pose a health hazard to people working on construction sites. In the United States in the 1950s, during the redevelopment of New York City, the housing environment of poor households was destroyed and the people, most of whom were racial minorities, were relocated. Technology can even destroy communities and their histories, which are both rooted in the land.

In the case of AI, which is a hot topic today, I think it’s important to understand the data for training the AI. Whether images or texts, someone produced them in their contexts. Thinking of the data as free material will inevitably lead to bad results. At the current stage, laws and guidelines differ from country to country, and at least in Japan, it’s not protected under copyright law. Therefore, I think this is a stage where ethical behavior is required from developers and users. Who used the data, where, and in what context? It’s also possible for anyone to create tons of nude images of models without permission. As with the Hollywood case mentioned earlier and the Jewish Museum, I think one key point is how to design for “consent.”

ShimizuJean-François Lyotard was deeply concerned about how techno-science enslaves the present to what it calls the future and loses its openness to chance. When it comes to AI, this could apply to the structure of what people call “AI cannibalism.” Even if ChatGPT studies various data and information from around the world and provides answers, the information created using ChatGPT is distributed on the Internet. That data is then read by ChatGPT and used for answers again, creating a vicious cycle and reducing accuracy. In that case, I think the key point will be how to make AI take advantage of chance.

I also think we should not forget the points made by American queer theorist Jack Halberstam. By the time Apple Computer showed up with a commercial based on George Orwell’s 1984, we were already living in a reality where Adam and Eve had bitten the apple. This is exactly the world symbolized by the Apple Computer logo. While discussing female cyborgs and Alan Turing, Halberstam questions the relationship between man and nature in the age of new technology. He tries to figure out how to create a story that incorporates multiple myths and diverse desires within a post-Christian worldview. I believe this vision is indispensable and important for us today.

KondoI now believe that technology does not speak about the future, but rather the memories of the past. Even in the Ghost in the Shell series, in Oshii’s film version, a public telephone appears in the story of the Puppet Master. This technology, which connected reality and the future in 1995, is now something of a distant memory. Through nostalgic technology, we can imagine the future while imagining the past. I think this method has potential for passing minority history on to the future.

Ginga Kondo

Artist, writer, art history researcher. Born in Gifu Prefecture in 1992. While in junior high school, she developed the incurable disease CFS/ME, which weakened her physical strength, and she has since used a wheelchair. In 2020, she obtained a master’s degree in the Department of Intermedia Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. She is a practicing artist while also researching art, literature, and subculture from the perspectives of feminism and sexuality. In particular, she uses various media to make her work, focusing on the relationship between lesbianism and art. Her solo exhibitions include “Everyday Life Like Politics, Like Dreams, Like Poetry” (Tokyo, 2018) and “Aesthetics of Gradation” (Tokyo, 2020). Her major group exhibitions include “Punctum: Diffuse Feminism” (Tokyo, 2020) and “Comfortable Exhibition” (Tokyo, 2021). Her co-authored works include “Interpreting Shin Evangelion” (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2021) and “We Are Already Together: Trans Anti-Discrimination Booklet” (Gendai Shokan, 2023).

Reina Saijo

Assistant Professor, Human Sciences, School of Engineering, Tokyo Denki University. With a background in analytical philosophy, she is engaged in research on feminist philosophy and the ethics of robotics. Her co-authored works include “Critical Words Fashion Studies” (edited by Hiroshi Ashida, Yoko Fujishima, Chie Miyawaki, Film Art Co., Ltd., 2022). Her essays include “How Should ‘Woman’ be Defined?” (Gendai Shiso 50(5), 2022) and “What is the Meaning of an Artifact Having Gender?” (Ritsumeikan University Institute of Humanities, Human and Social Sciences Bulletin 120, 2019), etc.

Tomoko Shimizu

Associate Professor, Department of Arts Studies and Curatorial Practices, Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Specialized in media and cultural theory and media cultural theory. Her books include “Culture and Violence: The Fluttering Union Jack” and “Disney and Animals: Undoing the Magic of the Kingdom.” Her co-translated works include “Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly” and “The Force of Nonviolence” by Judith Butler, “Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire” by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, and “Surveillance after September 11” by David Lyon.