攻殻機動隊 M.M.A. - Messed Mesh Ambitions_

The Ghost of Relations – On Mechanized Desires

[Credits]Text_Asahi Konuta / Ilya

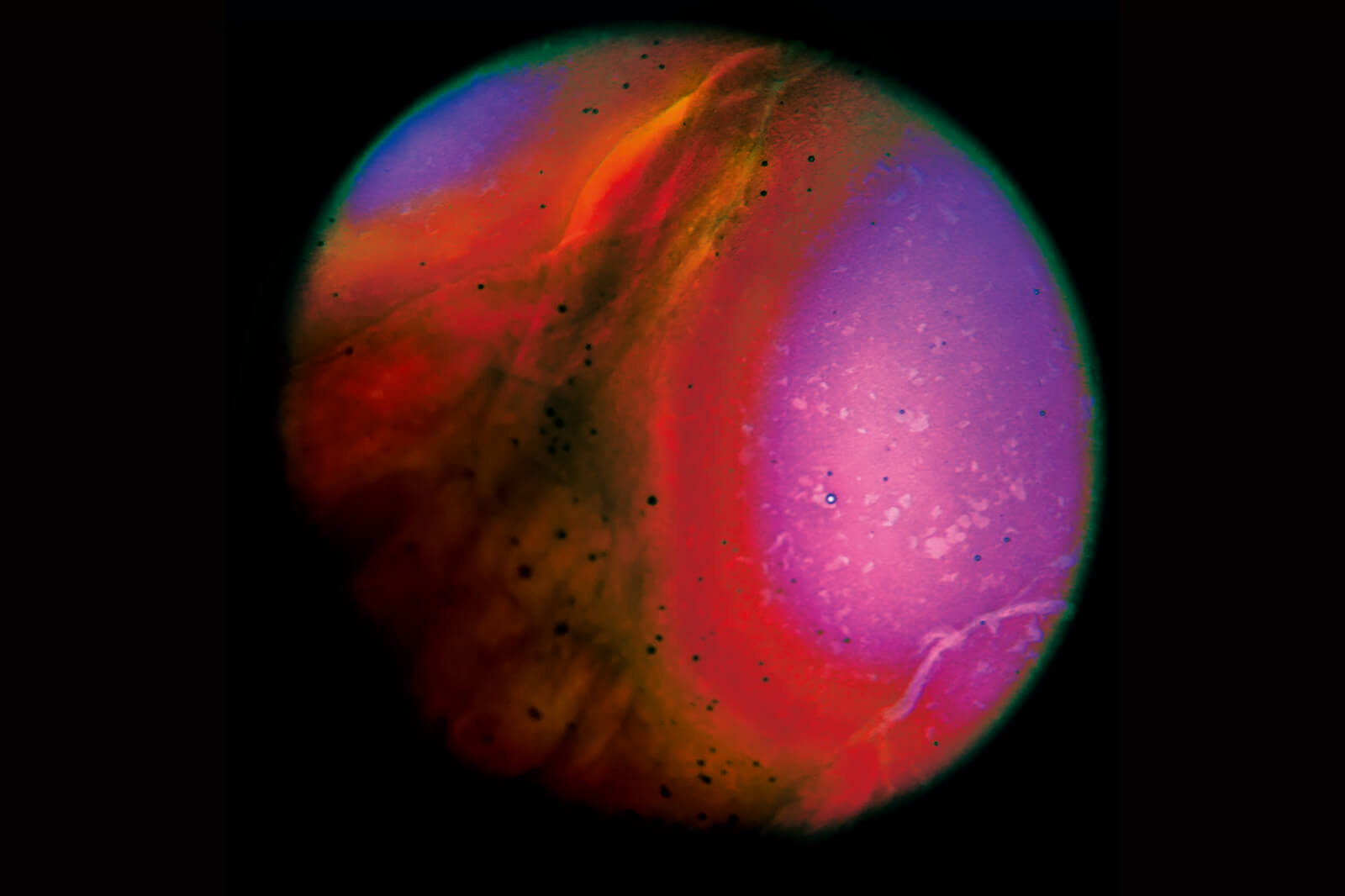

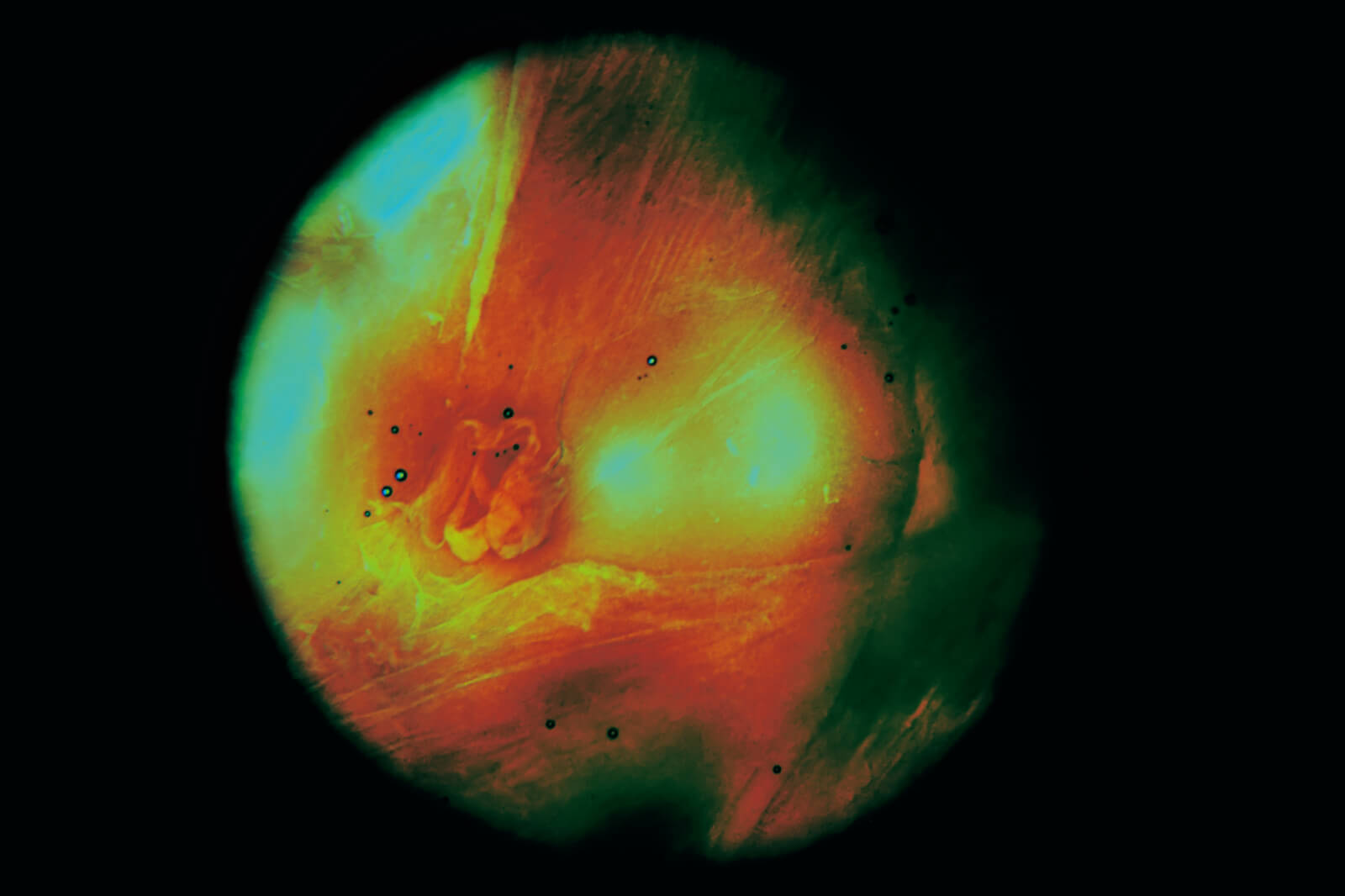

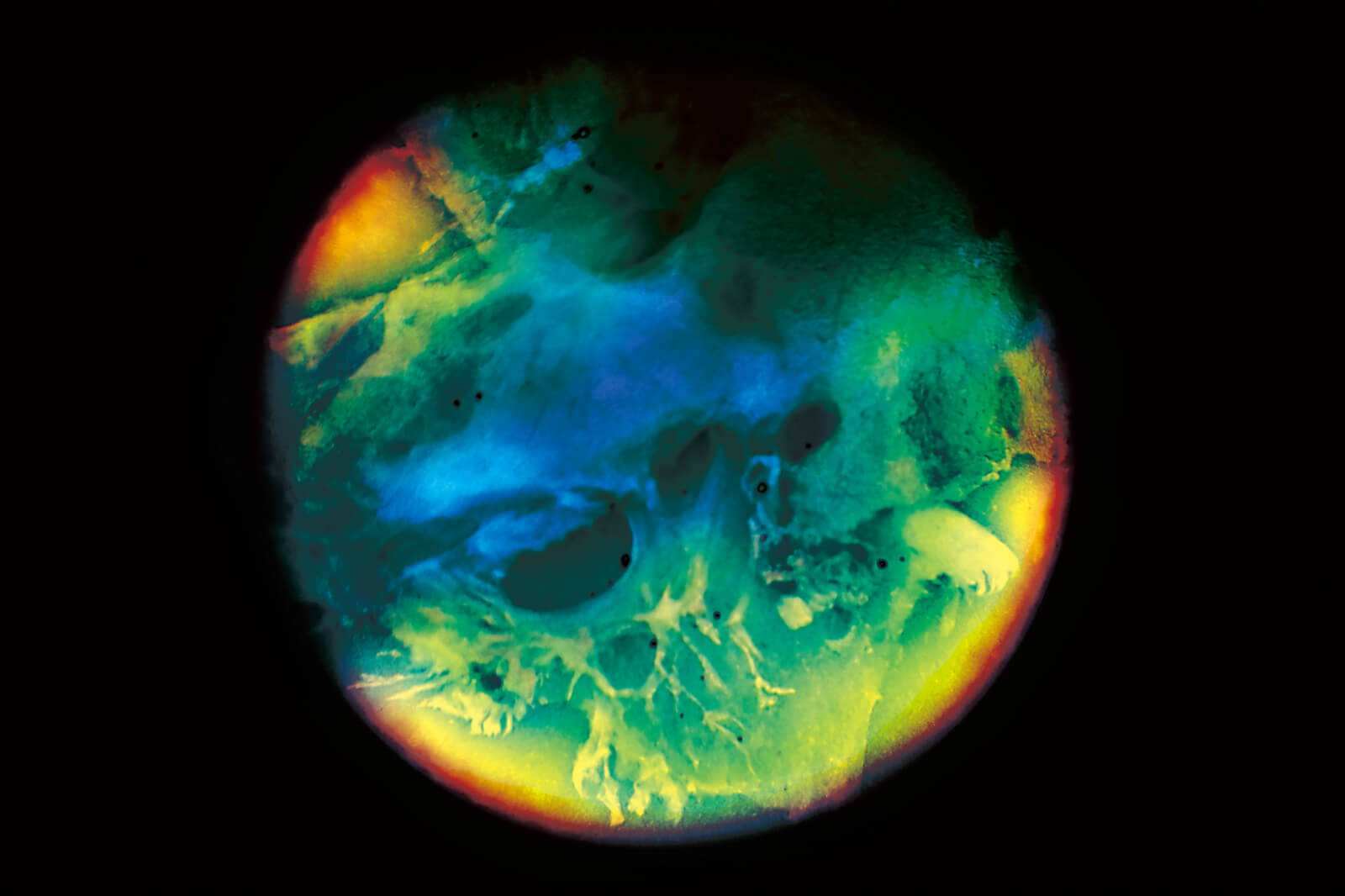

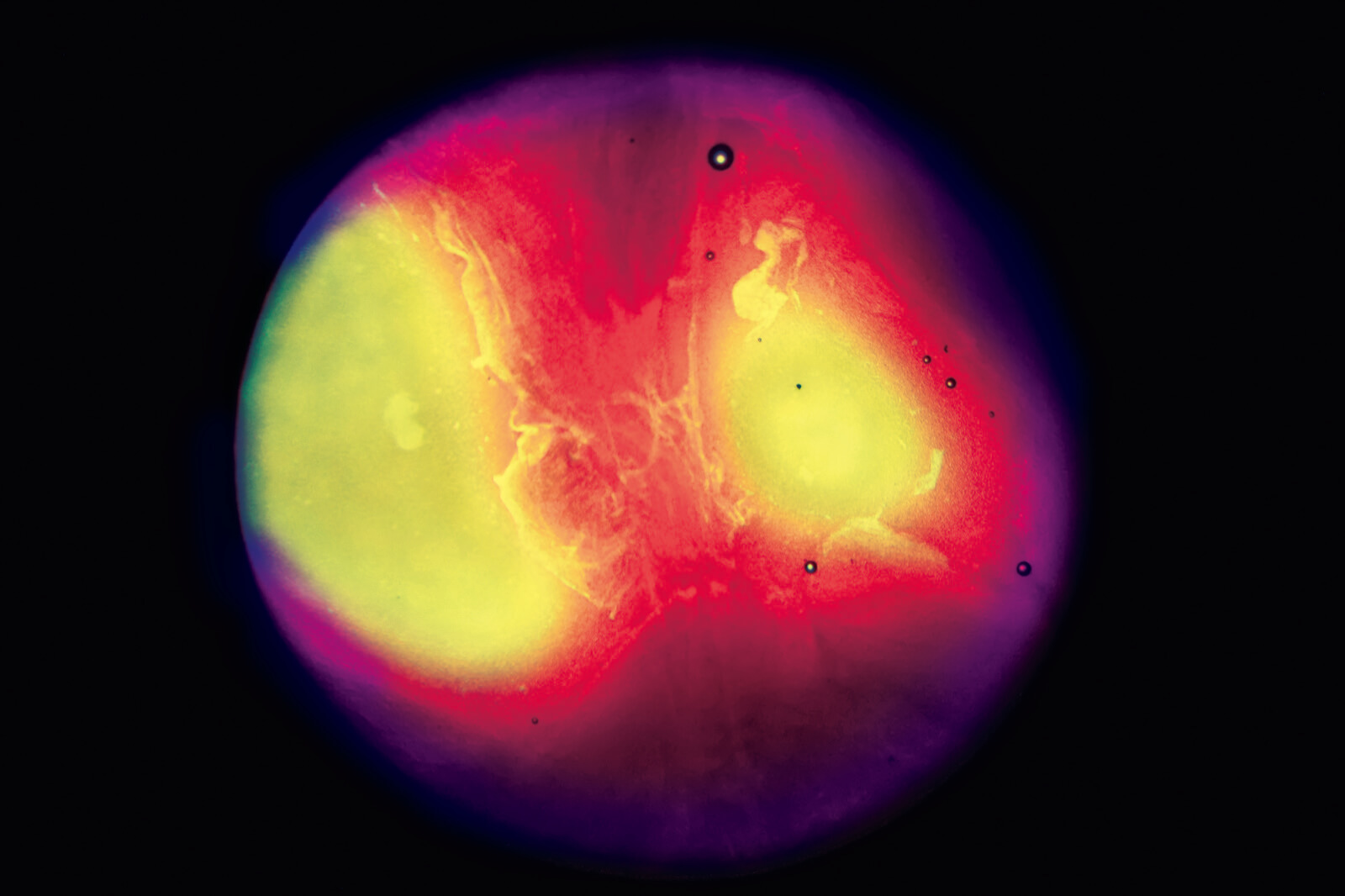

Images_Momo Okabe

Some theorists have reassessed sexuality from the perspective of “sameness” and celebrated the outlaw intimacy practiced by those living out impersonal narcissism. Notable among them is the late queer theorist Leo Bersani (1931-2022). Writing, “the self of the person loved is also the self of the one loving, and the loved one loves their self as it is loved, as the self of the one who loves,” Bersani rejects inclusion in any existing order as a premise of his thinking, putting forward a radically closed off and individual existence. Rather than persistently denying the isolation of the individual, Bersani brings up the idea of “depersonalization” at the extreme end of self-love and obliquely considers the potential of becoming “us” through this sameness. In this context, the world of Ghost in the Shell resonates with the conflicts of these inhuman Narcissuses living in the actual ”Stand Alone Complex.”

Accordingly, the important point is the “implausibility” of “relationship.” Rather than ignoring it, Konuta/Ilya’s continues exploring the potential of this implausibility—focusing on the instants where our “ghosts” dwell.

[Contents]

Latent Queer Desire in Ghost in the Shell

And the first utopia, the one most ancient and inseparable from the human heart may indeed be that of the disembodied physical body.*1

I felt nauseous at myself when I first had sex, unconsciously drifting into missionary position. I saw myself embodying socially male behavior. And to escape my hatred of masculinity, I began to dress as a woman. But this led those around me to demand femininity. They wanted me to be a beautiful and cute woman. There is no way out of the prison of male and female. Freedom from this prison is embodied by the young nude male forms shown in the girls’ manga I read in childhood. Depicted without penises or sexual differences, these nude images are a utopian sort of body not restrained by the prison of male and female. They almost resemble the bodies of genderless cyborgs.

Humans are restricted to bodies delineated by a penis or a vagina. Much of existing society—particularly in Japan—generally assigns sex based on whether individuals are born with a penis or vagina. This sex is then incorporated into official documents, and goes on to influence the person’s life. For example, a man with a penis will normally learn masculine behavior, love women, and take the role of a father in a family. This is accepted.

So what happens in a society in which the physical symbols of penis and vagina are negated? Society in the Ghost in the Shell series presents us with cybernetic bodies, for which physical sex can be changed. On the surface, this seems to negate the physical distinctions between male and female.

However, as a work, Ghost in the Shell is curiously tied to male and female sexual dimorphism. For example, almost all of the members of Public Security Section 9 have male appearances, and the androids that act as operators and in office roles are all female in form. Moreover, that female form is standardized, unlike the male. This can be taken as a manifestation of patriarchal thinking, in which men act with agency in society, while women are given only a secondary role. As a result, on its surface, the world of Ghost in the Shell is one in which penises and vaginas determine sex, even though bodies are not determined by the possession of either.

Yet the symbols found in the series are also entirely free of male and female physical distinctions. For example, there is the scene in the final act of the theatrical film Ghost in the Shell (1995) (“GIS” below) in which Major Motoko Kusanagi (“the Major”) is shown attempting to rip the armor off a tank, and appears physically symbolically ambiguous in gender terms. This paper seeks to elucidate the shape of the latent queer desires within the series, focusing on symbols.

The Bond Between Cyborgs

Eventually, the Major sheds her individual body by merging with the Puppet Master in GIS. This in turn allows the Major to utilize countless accessible bodies and cyberbrains rather than a single, specific one of each. As with the Puppet Master, there is no longer any indicator of the Major’s gender. The Major doesn’t just live in a body unrestrained by sex, she eventually becomes a being that is not reducible to gender indicators. It could be said that Batou refers to the Major as his “guardian angel” in Innocence because, as the term indicates, she no longer has either sex or gender.

However, the Major and Batou maintain an intimate relationship even without such gender indicators. This is also suggested in the Major’s words to Batou in the final act of Innocence, when she says “whenever you access the net, I‘ll be by your side.” Even as a genderless being, she remains Batou’s “buddy,” and an intimate presence.

So what are we to make of the intimacy between these two? What arrangement of desires gives their relationship*5 form?

Can their closeness provide us with a key to further explore this intimacy? Both the Major and Batou act and appear very differently, but there is a certain type of closeness between them. This closeness is most noticeable in the final act of the first season of SAC. We encounter a similar fixation on their cybernetic bodies in the two as they hunker down in one of the Major’s safehouses against pursuit from special forces troops. Specifically, the Major always opts for bodies that can wear a woman’s wristwatch, and Batou continues weightlifting, which has no purpose for a cyborg body. In other words, while both have cybernetic bodies that make them entirely independent of requiring a specific body, they are fixated on the individuality of their own bodies.

And clearly, we can see normative gender expression in this attachment to typical feminine/masculine bodies. However, their attachments to bodies cannot be reduced to gender dualistic sex differences.

The Major and Batou deviate from Section 9’s closed structure of homosocial desires. The scene in which Batou and the Major are speaking on a boat in GIS serves as an example of this. As they drink and talk about work in a typical masculine fashion, the Major brings up a private topic with Batou separate from their Section 9 mission. This glimpse of a private relationship separate from their official relationship gives the viewer a sense of an intimacy independent from Section 9. Is also seems that the Major’s openness toward Batou in this conversation is not unrelated to the fact that both are fully cybernetic. To borrow a phrase from Batou in Ghost in the Shell: ARISE, through this intimacy we may be seeing “the bond between cyborgs.” If so, then this intimacy (essentially, Batou’s love for the Major) must be taken not as male desire for a woman rooted in sexual differences, but as a desire arising from the similarities between full-body cyborgs. This line of thinking begins to reveal the Major and Batou not as simply work buddies, but as buddies independent of Section 9 and its closed (cis-hetero) masculinity. In other words, their intimacy begins to take on the appearance of queer buddies, rooted in the sameness of their body types rather than in sexual physical differences*6.

However, this intimacy—rooted in their sameness —does not conclude with the forming of a typical monogamous couple relationship. In this sense as well, the intimacy of cybernetic bodies is supported by the pair’s isolation. As is quite evident in GIS, the Major keeps others at a distance. Her behavior is that of one who believes that no one can understand them. Meanwhile, in Innocence, the Major takes a background role, while Batou also keeps others at a distance (excluding his beloved dog Gabriel). And thus, is their isolation not due to their cybernetics, and feelings of others (and themselves) being unable to comprehend existence in a mechanical body? (This may also be precisely the reason both are attached to one another’s cybernetic bodies.) Perhaps the Major and Batou never buddy up with Togusa, the non-cyborg, or fail to mesh when they try, because the isolation of a full cyborg is all the more visible in front of a non-cyborg? As a result, the “bond between cyborgs” that connects them may be built on emotions not readily understandable to just anyone. Accordingly, the pair’s relationship is a sort of paradoxical intimacy connecting them while leaving them separate. (This in turn could be argued as the reason that the Major and Batou never end up together in the Ghost in the Shell series. The reason for this being that their intimacy is premised on their mutual isolation.)

The Non-Identitarian Sameness of the Tachikomas

However, Batou’s desires for the Tachikomas impart them with the concept of individuality. In the first season of SAC, Batou gives one Tachikoma organic oil after forming a buddy relationship with it. This causes that Tachikoma’s AI to begin to develop individuality. Furthermore, when the memories of this Tachikoma are synchronized to others after it gains individuality, they too also have their egos awakened. Where the original manga and Oshii film depict the drive to become a universal being by abandoning individual existence, the first season of SAC depicts the ways individuality arises out of identical, universal existences. (And in actuality, where the Major casts off her body in the original manga and Oshii film before exiting in a male or child’s body, at the end of the first season of SAC she reclaims her usual body and abandons the remote doll child body she had used to disguised herself. Doing so, she says that “nothing feels like this body.”)

The Tachikomas that awaken their individuality do so primarily out of a desire to have Batou as a buddy. The Tachikomas are seen as having problems in their performance as weapons due to this development of self-awareness, and are sent to a lab. However, in the conclusion of the season, they end up rushing to Batou’s aid. The three remaining Tachikomas, now mostly disassembled, show they want to fight as his buddies. In the end, they sacrifice themselves and are destroyed to protect Batou.

For a paper concerned primarily with intimacy, the key point here is that the AIs’ sacrifice does not mean they have acquired souls or ghosts, but rather, that standardized beings without individuality have gained individuality through the process of directing desires toward an intimate other. The synchronization of the Tachikoma that gained individuality via Batou’s intervention does not result in the dissolution of its individuality into universality, but instead is a process that transforms each universal being into its own individual by desiring Batou as a buddy. Non-binary entities that lack a sex like the Tachikomas are also able to obtain individuality via the distribution of the desires rooted in their mechanized bodies, much as Batou and the Major do (and in the sense of saving Batou in a crisis similarly to the Major in Innocence, the Tachikomas are also Batou’s “guardian angels” in SAC season 1).

However, Tachikoma individuation is not the same thing as acquisition of identity; rather, it occurs when their identity is shattered. While none of the main members of Section 9 die no matter how many crises they face within the SAC series, the Tachikomas’ bodies are destroyed many times throughout the story. Additionally, the process of synchronization shows that the Tachikomas’ individual identities are capable of being repeatedly destroyed. Accordingly, the Tachikomas’ separate individuality could be said to be formed not by validation of the self in relation to others, but by the arrangement of a relationship formed through the desires of another (Batou). Even if identity is lost, the relationship via desire is not. Accordingly, in SAC, the Tachikomas revive as many times as they are destroyed, and each time they become Batou’s buddies.

The Tachikomas form of existence conforms to Leo Bersani’s concept of “nonidentitarian sameness”*7, which he details in essays on homosexuality. For Bersani, homosexual desires dispel the idea of individual distinction equating to identity, and the loss of this identity allows the formation of homogenous desires he refers to as “sameness.” Among the Tachikomas, individual experiences of self-loss and identity destruction are adjacent to their return (an experience of a type of self-reproduction) to homogenous desires for Batou synchronized across the group.

It follows then that the desire in play between the Tachikomas and Batou is an expression of queer desire that deviates from the series’ ostensible representation of (cis-hetero) male and female relationship models.

The Body as a Wrinkle

The individual is a woman and former lover of his. She had acquired an identical cybernetic body to his in order to understand why he had left her. Claiming that “I found your ghost within myself,” she has chosen to become one with him physically, directing her love for him toward herself in his absence. In the sense that this is a heterosexual desire resulting in unification with the man desired, her heterosexual desires incorporate elements that are inconceivable from a normative perspective.

Given they do not relate to sexual organs, her desires are not heterosexual. Having become the same as Pazu, the woman states that the “ghost” doesn’t dwell within the “shell of the brain,” but rather “in the skin, and especially the creases on this face.” In other words, what she wanted was not a body with his penis, but rather the “creases” etched into his skin. Her desires radiate a queerness with no interest in bodies with sexual organs.

I can relate to this woman’s desires for the creases in her lover’s skin and her conception of them as a way to be one with him. This is because my own body also intersects with non-sexual organ desires.

There are protrusions on my back. These protrusions are similar to the plates of a stegosaurus along the spine. These are marks of my queerness. Even saying this, these are the scars from compression fractures caused by a suicide attempt in an era when I had sex with queer people, and my family asked that I don’t touch them, because they didn’t know what kind of diseases I might have. Yet the scars on my back aren’t suffused with sadness. These wounds are also the marks of my relationships with cross-dressers, trans individuals, and cis men and women outside the closed, cramped community of my blood relations. All of this is to say that I retain a “relational ghost” on my back in these wounds through my relationships with a variety of queer individuals and desires. Just like the protrusions on my backbone, the woman’s attraction to Pazu’s body is a depiction of the traces of desire to a physical area that is removed from the sexual organs. Wounds due to stigma serve as traces of my queerness, rather than causing me sadness.

In this way, the “ghost of queer relationships” I acquired through non-genital desires overlaps with the sensations of those with fully cybernetic bodies in Ghost in the Shell. In the final act of season 2 of SAC, one of the main characters, Hideo Kuze, speaks with the Major about his private physical and mental struggles. As someone who has been fully cybernetic since childhood, he says “he has always felt his mind and body were misaligned.” However, he also says that the Asian refugees he met on his travels praised him, saying his artificial face was handsome and that “they could see his ghost in it.” That was the first time that he “realized mind and body might be inseparable,” and that “I was also a person with a body,” he asserts.

Now, let us return to the topic of Pazu, and the woman who took his identity. To borrow her phrasing, through his encounters with the Asian refugees and their recognition of his identity, Kuze’s “ghost” resides “in the skin, and especially the creases on this face” rather than within “the shell of the brain.” The same face sculptor built the faces of both the woman who imitates Pazu, and Kuze, who felt his mind and body didn’t align, and he claimed to be able to see the depth of the wounded’s mental injuries in their physical wounds from the war. The face sculptor’s desires can be said to have been fulfilled the moment Kuze recognizes the wounds in his skin (“wrinkles”) are a medium for recognizing his own ghost, after the refugees accept his face as handsome.

As someone who has experienced gender dysphoria since childhood, I have always struggled with feelings that I am not male, even as I present masculinely within society and inhabit a body that assumes missionary position in intimate moments. Accordingly, I can understand very well the meaning of the “misalignment of mind and body” that Kuze senses. But to be precise, I am not repeating the typical phrasing that the transgender struggle is a misalignment between the genders that we feel internally and in our physical sexes. Rather, Kuze’s “misalignment” emphasizes the sublimation of approaches outside mind-body dualism. In short, the fact that the “ghost” resides “in the skin, and especially the creases on this face” rather than within “the shell of the brain” could also be said to mean that “the (gender of the) heart and (gender of the) body” are inseparable, and that to approach the sensation of a ”misalignment” of mind and body requires “a heart revealed through the body.”*8 In fact, the desire for queer relatedness embodied in my scars and life is one of the means I used to escape from the “misalignment of body and mind” I felt from being assigned to the male gender at birth. Accordingly, the “misalignment of mind and body” that Kuze feels (and likely all full-body cyborgs in Ghost in the Shell, including the Major and Batou feel) does not end at mind-body dualism; instead, it intersects with the desires that queer individuals like myself feel when first realizing our minds and bodies are inseparable.

On this point, considering desire from the physical aspects of skin and its creases, which is independent of distinct individual physical identity, might help to develop a relationship model that is separate from identity. Kuze, the woman who transforms into Pazu, and myself are all drawn together through our “formal affinities”*9 by way of our skin and its creases and wrinkles. This intertwines with the relationships between the Major and Batou or between the Tachikomas and Batou, which are woven from a sameness, not from identities formed by distinctions. The mechanized desires in Ghost in the Shell are not related to individual ghosts that are differentiated from one another; rather, these desires present a way to connect with those outside ourselves through embodied “ghosts of relationship.”

Ghost in the Shell takes place in a fictional world. Full-body cyborgs, self-enhancing AIs, and cyborg bodies with interchangeable sexes are all out of reach in today’s society. However, though it depicts a fictional future, the symbolic desires in Ghost in the Shell intersect with queer desires we find in the present. And thus, there is a latent hope beneath the surface that the broadly homosocial setting of Ghost in the Shell can also serve as a utopian system for embodying the reality of queer desires.

[Notes]

*1

Michel Foucault, Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias. (trans. Yoshiyuki Sato) Suiseisha, 2013. p.17

*2

This term is used to refer to the two films directed by Mamoru Oshii, Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Innocence.

*3

Abbreviation for the TV anime series Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex. The second season of this series, Ghost in the Shell: S.A.C. 2nd GIG is referred to here as “the second season of SAC.”

*4

For example, the Major is depicted as having sexual relationships with women in the original manga and SAC, but is shown as primarily having male partners in the second season of SAC and in the ARISE series. Her partner relationships with women are not shown explicitly, and her lesbian relationships are sometimes demoted to a secondary status in the Ghost in the Shell series.

*5

In this paper, the use of the Japanese collective male pronoun “kare-ra” is not intended as a male pronoun, but rather as a neutral plural pronoun like “they.”

*6

On this point, the intimate relationship the Major and Kuze share in the second season of SAC could also be taken as rooted in the “sameness” of full-body cyborgs rather than in heterosexual relationships.

*7

Leo Bersani, Is the Rectum a grave? and Other Essays, The University of Chicago Press, 2010: 183.

*8

The physicality of the skin, creases, and wrinkles does not need to be interpreted materialistically. This is because the sensation of this skin and its creases is also part of the body as an image, formed between Pazu and the woman, or between Kuze and the Asian refugees. On this point, the view of bodies in Ghost in the Shell could be said to present physicality as “body image.”

Kazuki Fujitaka, “What is ‘Gender Dysphoria?’: Toward the Adoption of Transgender Phenomenology” in Introduction to Feminist Phenomenology, ed. Minae Inahara et al. Nakanishiya Shuppan, 2020. pp.115-126

*9

Yuki Nagao, “Bersani’s Violent Care/Cyborgs’ Skewed Bodies” in Gender & Sexuality (No. 18, 2023).

Leo Bersani, HOMOS, Harvard University Press, 1995:121

Asahi Konuta / Ilya

Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1992. Currently enrolled in doctoral studies at the Osaka University Graduate School of Human Sciences. Lives a genderqueer life not constrained to male or female gender identiy. Focused on the fields of modern thought, queer theory, transgender studies, Emmanuel Lévinas, and Leo Bersani. Primary works include, “Perspectives on Mourning and Survival for Queer People in Late Levinasian Ethics: Through Butler’s and Freud’s Perspectives on Mourning” (Phenomenology and Sociology (6)), “The Problem of Descriptions of Sexuality in Early Levinas: On Normativity and Potential” (Phenomenology and Sociology (5)), as well as jointly authored works including “An Introduction to Feminist Phenomenology: Re-examining ‘Normal’ from Experience” (2020) and “Feminist Phenomenology: Toward a Place That Resonates With Experience” (both Nakanishiya Shuppan, 2023).