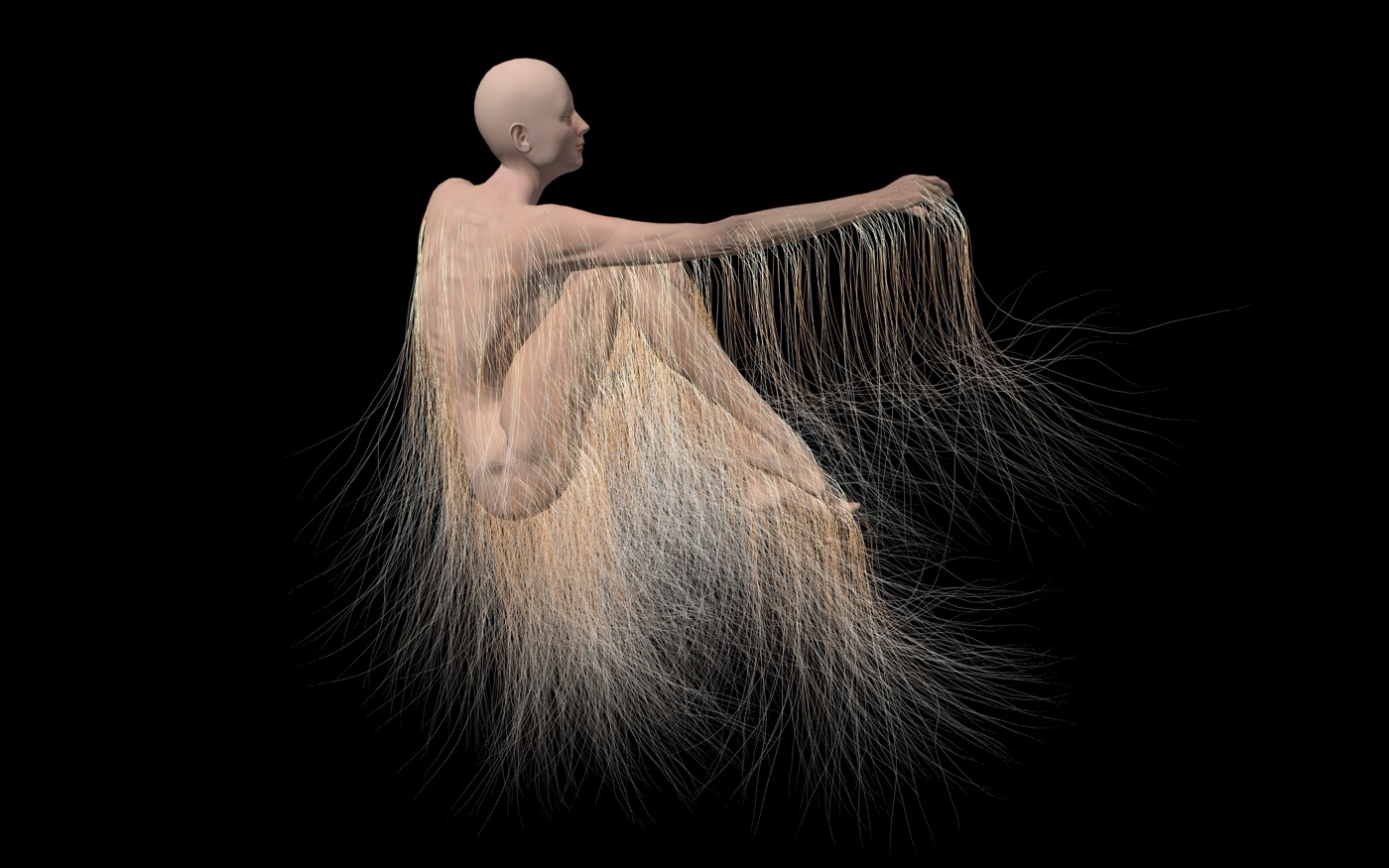

攻殻機動隊 M.M.A. - Messed Mesh Ambitions_

Shota Yamauchi, Tina growing, 2022

Mock Meat, That Imitates Meat but Is Not Meat—An Introduction to Criticism of Humano-Genderism

[Credits]Text_Yuu Matsuura

Images_Shota Yamauchi

Since Judith Butler’s criticism of the prohibition of homosexuality prior to incest, the relativization of heteronormativity has progressed, at least in theory. However, when Yuu Matsuura brings up fictosexuality, sexual attraction toward two-dimensional characters, it becomes evident that the diversification of desires has yet to extend beyond the realm of human-oriented sexuality. In other words, within a world of human-oriented sexualism, the possibility of our desires being directed towards two-dimensional characters is foreclosed. When we become aware of this foreclosure, questions begin to arise.

Although we call them two-dimensional characters, they are modeled after humans. Therefore, people who love two-dimensional characters are expected to develop desires based on norms of human-oriented sexualism in real life. However, as the number of fictional characters proliferates, the desires toward them begin to take on a unique quality. Eventually, the enthusiasts of these characters realize the location of their excluded desires. What Matsuura focuses on is not the creator of the character but the desire of the recipient, who stands before the gates of the rules of human-oriented sexuality. What does it mean for humans to desire non-human objects? How has this been made possible? The author takes a sharp approach to the mechanism of desire. In the world of “Ghost in the Shell,” where prosthetic bodies and computerization technologies have become widespread and the humanity of humans has become increasingly rare, desires that are not suitable for humans are sure to emerge as even more pressing and actual issues.

[Contents]

- Positioning the issue of human-oriented sexualism

- Distinguishing between lies and fiction: problems of truth/falsity and problems of ontology

- Mimetic empathy: How do fictional characters come to life?

- “Rendering meaningless” of being two-dimensional

- Implications for issues of gender and sexuality surrounding technological artifacts

Shota Yamauchi, Tina_growing_Other 01, 2022

Positioning the issue of human-oriented sexualism

Nevertheless, the relationship between humans, AI, and robots tends to be discussed as if technological breakthroughs suddenly created entirely new problems. Of course, there may be new phenomena, but people have been interacting with objects and artifacts for a long time. If this is the case, when thinking about recent artifacts, it would be meaningful to put aside questions about technology before starting a discussion.

I have so far conducted interviews with people who enjoy so-called “two-dimensional” sexual creations such as manga and anime but who say they do not feel sexually attracted to real people. Based on the results of my survey, I am conducting research applying queer theory to the recent phenomenon in which two-dimensional sexuality is different from sexuality that targets flesh-and-blood people.*1 In this article, I will examine the existence of two-dimensional characters and their politics based on my past research results. With that in mind, I shall revisit the issue of gender and sexuality involving technological artifacts such as AI and robots that I temporarily set aside.

Before getting into the main topic, I would like to briefly introduce the issues surrounding the normativity of sexuality. In recent years, more discussions have been held about issues that cannot be explained by heteronormativity alone. Among these is a critique of the stereotype that the object of sexual or romantic attraction is a flesh-and-blood human being. For example, in the study of objectum sexuality, ” the belief that sexual relationships with human beings are preferable or more natural than those involving inanimate objects” is conceptualized as humanonormativity (Motschenbacher 2014: 57).

Even in Japan, from the perspective of people who enjoy two-dimensional sexual creations but are not sexually attracted to real people, the term “human-oriented sexuality,” which refers to the sexuality of being attracted to real human beings, has been proposed at the grassroots level. Furthermore, the social norm that considers sexual attraction towards flesh-and-blood human beings to be “normal” sexuality is called human-oriented sexualism. In this paper, we will proceed with the discussion, keeping in mind these recent issues surrounding sexuality.

Shota Yamauchi, Tina_growing_Other 02, 2022

Distinguishing between lies and fiction: issues of truth and falsity and issues of ontology

A lie is a statement about something that is not true. The question then is “whether it is true or not.” In short, lies are a matter of truth and falsehood. Also, lies only work when the other person is deceived. In order to tell a lie effectively, you must prevent the person being lied to from realizing that they have been lied to. For example, the main theme in “Ghost in the Shell” is the question of truth and falsehood. Do ghosts really exist? Am I really human? Does my family really exist? All of these are questions about whether something is true or false, and they also make us worry that someone might be deceiving us.

On the other hand, creative activity is the act of creating a type of existence that does not belong to reality or the world of everyday life. In order for the experience of accepting a created work to take place, the recipient must be aware that what he or she is viewing is a created work that is different from reality.*2 For example, the character Major Motoko Kusanagi is a kind of artifact created by people’s creative acts and belongs to a category that is ontologically different from that of real humans. Those who accept “Ghost in the Shell” are clearly aware of the ontological problem that fiction and reality are ontologically different. In this way, the question of truth and falsity is different from the question of the existence of fiction.

In addition to this, another issue that tends to cause confusion in discussions is the issue of presence. This is a question of whether a certain object feels as if it exists vividly. We can feel a sense of presence not only in things in our daily lives but also in imaginary beings. For example, we sometimes feel that fictional characters exist very vividly. This sense of presence is not only created through the imagination of individuals but can also be created technologically using VR and stereophonic sound, for example.

With that in mind, I shall proceed to the main topic. How do the beings called fictional characters come to life? In other words, how do these beings, who are unlike humans and, moreover, have no biological or technological basis for acquiring consciousness or inner self, end up coming to life?

Mimetic empathy: How do fictional characters come to life?

That is why character theory has focused on creative acts and modes of expression. I won’t go into details, but in manga research, there is an argument that, for example, by repeatedly drawing new iconography of the same character, we give new aspects of the character, creating a time span within the story world and giving the character a life with a time span (e.g., Iwashita 2013). Alternatively, there is an argument that the existence of a character is firmly established not only through the creation of a story world but also through the creation of fan fictions by many people (e.g., Adachi 2020). To sum up the current trend in character theory in one word, it is that iconographic characters are performatively constructed through the act of material depiction.

However, even if it is just a physical expression produced by the act of drawing, it is still just a “mere picture,” or in the case of animation, a continuous change of “mere pictures” or a flickering screen. This is because the discussion so far has only explained the process by which the external form of a two-dimensional character is created. How can we bring an inner world to two-dimensional characters that exist as iconography or images without any biological or technological basis for having an inner world? How is a soul imbued with a two-dimensional character? The theories that explain this are Nobuyuki Izumi’s theory of “mimesis of the mind” and Rane Willerslev’s theory of “mimetic empathy.”*3 The former is a study on the movements of emotions of manga readers, while the latter is an anthropological study on the animism of the Siberia Yukaghir people, and the research fields and themes are completely different. However, both discuss methods of attributing the inner world to non-human beings, and moreover, they present almost the same theory.

First, let’s look at Izumi’s “mimesis of the mind.” “Mimesis of the mind” is different from self-projection or empathy and is used when reading manga or novels as a phenomenon of “rather than throwing yourself into the character, create the character’s emotions within yourself (to the extent that you can understand)” (Izumi 2014: 145, emphasis added). Izumi points out that “there can be no real emotion within the two dimensions of manga or novels, and the mind and body of the reader are a simulator of that emotion” (Izumi 2014: 145). “Mimesis of the mind” gives an inner being to a being that does not have the substance to generate inner feelings such as emotions and sensations. In order to bring a character to life, it is not enough for the creator to simply depict it; the emotional practice of “mimesis of the mind” by the recipient is essential.

Anthropologist Rane Willerslev has proposed a theory similar to that of the mind of manga readers. Based on his fieldwork on the animism of the Siberian Yukaghir hunting people, Willerslev discusses how the Yukaghir people attribute their inner selves to non-human beings. This is “mimetic empathy.”

Interiority in animism is not a property inherent in things but “is constituted in and through the relationships” between people and things (Willerslev 2007: 21). Willerslev uses the term “mimesis” to label how the Yukaghir people attribute to the animals they hunt a “personhood” that corresponds to the so-called inner world or soul, which is different from both the legal concept of personality and the philosophical/ethical concept of personality. Mimesis is “the practical side of animism” and “a prerequisite for” animism (Willerslev 2007: 191). Mimesis that Willerslev refers to is more accurately called “mimetic empathy.” Mimetic empathy is not a outward imitation but a practice that involves “the ability to put oneself imaginatively in the place of another, reproducing in one’s own imagination the other’s perspective.” (Willerslev 2007: 106). Therefore, it can be said that “mimetic empathy provide the entrée to the perspective of the other” (Willerslev 2007: 107).

Of particular note is Willerslev’s emphasis that mimetic empathy is different from identification. Since empathy arises “because the other’s experiences are not mine,” “the boundary between myself and the other, between my experience and that of the other, does not vanish” (Willerslev 2007: 107-108). Empathy, which is not complete identification, requires the difference between oneself and the other person.

Willerslev uses the example of people who watch Hollywood romantic comedies as a supporting line when considering animism. This example is particularly instructive for this article. When watching a romantic comedy, “[t]hrough this empathy, we are seduced into abandoning our own universe and incorporate, empathetically, the universe of the characters in the film, and we begin to experience as completely as they do their desire for love, and their propensity to sacrifice everything for love” (Willerslev 2007: 104). Of course, mimetic empathy is distinguished from ” uncontrolled feelings of love” because one does not completely lose oneself by identifying with another (Willerslev 2007: 108). Mimetic empathy is essentially selecting “particular bodily states, feelings, or conditions in another, which I then reproduce” in one’s own imagination (Willerslev 2007: 108).

Although the subjects discussed are different, in light of the interest in this paper, Willerslev’s theory of mimetic empathy points in the same direction as Izumi’s theory of mimesis of the mind. Echoing Willerslev’s example of romantic comedies, Izumi also argues that his own theory is especially important when considering the reception of “romance” and “pornographic works.” From this point, the closeness between the two can be further discerned. In order to understand and enjoy the “emotions” and “feelings” of manga characters, readers do not need to project themselves or empathize with the characters. “Mimesis of romantic feeling” does not require you to “fall in love with the character yourself” or to “become the character” (Izumi 2014: 145). Therefore, in order to enjoy these works, it is important to be able to understand the feelings of both rather than being immersed only in either the “tops” or “bottoms” parties. As Izumi states in their criticism, whether you empathize with the “tops” party, empathize with the “bottoms”, or you look at it objectively from a bird’s-eye view, these three mutually exclusive options do not correspond to the actual experience of receiving works. The subject’s use of imagination to imitate the emotions of the object is a way of attributing the inner self to a non-human and a way of infusing (animating) a two-dimensional character with a soul.

However, the fact that Izumi and Willerslev’s theories can be cross-referenced does not imply that people who love two-dimensional characters are within the bounds of animistic beliefs and practices. The activities of Yukaghir and the practice surrounding two-dimensional characters are two different things, and apart from imitative empathy, they have almost nothing in common. Furthermore, the idea of linking a love of two-dimensional characters (or AI or robots) with animism tends to fall into the erroneous theory that Japanese people are special, such as the “techno-animism” theory.*4

One more point to note is that mimetic empathy does not explain the uniqueness of two-dimensional representations. Mimetic empathy is not limited to activities surrounding the two-dimensional, as it is carried out in a wide variety of situations that traverse two and three dimensions, such as not only reading manga but also the reception of Hollywood movies and animistic practices. In order to think about the two-dimensional, we must separately consider the materiality of the two-dimensional.

Naturally, two-dimensional characters exist in a different way than flesh-and-blood humans. This is what Eiji Otsuka calls the “symbolic body.” It is a kind of abstract existence that has pictures and symbols as its body. Of course, from a metaphysical perspective, there is also the position that “it does not actually exist, but it has the effect as if it does exist.” When thinking about people’s practices, either “exists” or “has the effect of existing” is fine. But what is important is that the sign is a physical thing. Originally created as a symbol to point to a human being, the painting becomes a new category of “two-dimensional character” by being animated by the mimetic empathy of the recipient. This situation arises because graphic expression through symbols is always supported by materials such as ink, magazine pages, and screens. This is because the substance itself (rather than the immaterial, abstract object that the symbol points to) is animated when it is accepted (Matsuura 2023).

The misdelivery that occurs between production and mimetic empathy not only establishes the existence of two-dimensional characters but also brings about transformations on the part of humans who enjoy these two-dimensional characters. In this situation, there is a desire for two-dimensionals established, which is different from the sexual desire that exists between humans. In other words, a two-dimensional character as a new type of entity is created, and the way people perceive and desire is also rewritten. As a result of such ontological and epistemological transformations, a kind of queer subversion can occur that relativizes human-oriented sexuality that has been considered “natural” and “normal.”*5

In human-oriented sexualist cultures, the difference between two dimensions and three dimensions is considered virtually meaningless, and two-dimensional sexuality has been rendered invisible. Regarding this issue, Taiwanese fictosexual researcher and activist SH Liao illustrates the phenomenon of erasure through human-oriented sexualism by citing a conversation about Sù-Shí (Taiwanese Buddhist vegetarian cuisine) in episode 8 of “Ghost in the Shell: S.A.C. 2nd GIG.”

Batou: “(omitted) [Taiwanese vegetarian food] differs from Japan’s vegetarian cuisine in that the ingredients are not simply cooked as is, but beans and mushrooms are modified to recreate meat and fish.”

Togusa: “(omitted) But why did a Taiwanese monk come up with such a complicated cooking method? If you don’t know the taste of meat from the beginning, there’s no need for it.”

Batou: “That’s right. However, anyone can eat anything before entering Buddhism. No matter how much you train, you can’t erase the memories of those days.”

Liao points out that in this conversation, the historical background of Taiwanese vegetarian food is ignored, and the existence of people who love Taiwanese vegetarian food, regardless of meat or fish, is ignored.

Batou’s answer decontextualized the Humanistic Buddhist (rén-jiān-fó-jiào) history of this “vegetarian meat”, which was first promoted to the general public. At the same time, it denies the existence of Taiwan’s “vegetarian meat” as a “cuisine” independent of “meat” among various cooking techniques for a long time — Ignoring the fact that “vegetarian meat” cuisine is not only a substitute for “meat”, but also a “cuisine” that anyone can enjoy, is foreclosures the existence of “vegetarian meat lovers” who simply like vegetarian meat. (Quoted from Liao 2023 English version)

In the same way, Liao points out that sexuality surrounding the two-dimensional (love of mock meat) is based on human-oriented sexuality (love of eating meat), and the existence of the former, which operates independently of the latter, is erased. *6 In some cases, the two-dimensional character (mock meat) is a representation of a flesh-and-blood human being (meat). Therefore, it is sometimes even crudely reduced to the conclusion that there is no difference between desiring a two-dimensional character and desiring a flesh-and-blood human being.

When sexuality surrounding the two dimensional is erased under human-oriented sexualism, what is being abstracted away is the materiality of two-dimensional existence. Social and cultural factors steeped in human-oriented sexualism limit the effects of the material elements that two-dimensional characters are supposed to have, and their materiality is seen as meaningless. So, how should we think about this meaningless materiality?

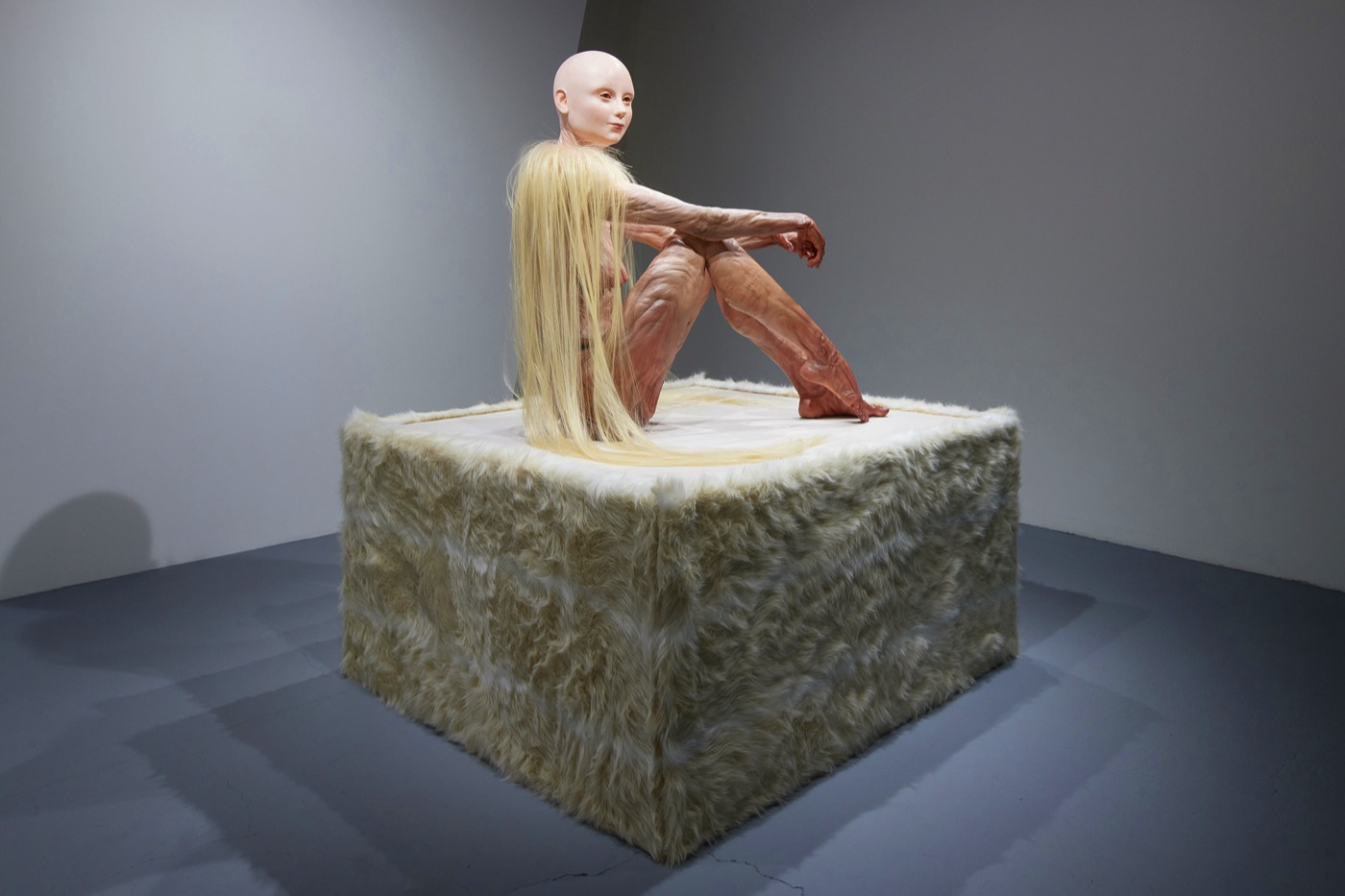

Shota Yamauchi, Tina sculpture, 2022 / Photo by Ryo Yagara

“Rendering meaningless” of being two-dimensional

Meaningful meaninglessness is meaninglessness that is experienced by people as “unthinkable” and meaningless due to “infinite ambiguity” (Chiba 2018: 11). Meaningful Meaninglessness corresponds to Lacan’s “The Real” or Kant’s “thing-in-itself.” In Butler’s terms, it is something that is foreclosed as an incomprehensible and abject other and is, so to speak, meaningless in a negative theological system.

On the other hand, meaningless meaninglessness is “meaninglessness that stops the rain of meaning” (Chiba 2018: 11), and it does not bring about abjection but simply leads to a cessation of thinking. This corresponds to the Material as described by Catherine Malabou and the reality outside of correlationism. Meaningless meaninglessness is material and corresponds to “body,” “form,” and “the possibility of destruction and change of material things.” It should be noted that the word “body” that Chiba refers to has a fairly broad meaning and includes not only objects and substances but also “any abstract form is a body,” including “gatherings” of people and things and imaginary images (Chiba 2018: 14).

Based on this theory, Chiba reinterprets Hiroki Azuma’s theory of “animalization” in a queer way. In “Animalizing Postmodernity (Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals),” Azuma positions the excitement of “otaku” toward two-dimensional sexual creations as “genital needs” (Azuma 2009: 89). In Azuma’s argument, this genital neesd is ” simply and directly, (…) close to the behavioral principle of drug addicts” (Azuma 2009: 88). It seems that there is no expectation that there will be any opportunity to question the dominant heteronormativity. In contrast, Chiba focuses on Azuma’s argument that “having once encountered some character designs or the voices of some voice actors, that picture or voice circulates through that otaku’s head as if the neural wiring had completely changed” (Azuma 2009: 88). Following Catherine Malabou, Chiba reconsiders this as “the plasticity of the brain that intervenes externally in the mind” (Chiba 2018: 20). Chiba argues that queer subversion can occur on a layer different from psychoanalytic heteronormativity. In other words, it is possible that even if drug-addictive “cognitive habituation” is used to “maintain heterosexual and reproductive normativity at the same time, “reproductive de-normization” is dissociatively parallel.” (Chiba 2018: 110 emphasis in original).

Chiba’s argument is a “speculation” of queer possibilities that arise in ways different from human volitional practices. However, the focus of this paper allows us to raise some doubts. First, Chiba’s argument focuses only on human cognition and does not address the non-human materiality of the two dimensional. This problem stems from the fact that the discussion in this section of “Animalizing Postmodernism” does not take into account two-dimensional materiality. In other words, it does not mention “drugs,” which are the objects of “needs,” and does not take into account the diversity of “drugs.” A second, more important problem is that the issue of how the possibility of “drug-dependent” queerness is erased is left out. Chiba’s argument only emphasizes the aspect that material things constrain the realm of social meaning but neglects the aspect that the effects of material things are constrained by the social and semantic realm.

Although it is true that Taiwanese vegetarian cuisine was born out of the historical context of the existence of meat and fish dishes, it has had a history different from that of meat and fish dishes and has materialized in a different way than dishes using meat or fish. Nevertheless, the historicity and materiality of Taiwanese vegetarian food are erased by the assumption that the desire for meat and fish dishes is fundamental. Similarly, under a human-oriented sexualism interpretation scheme, two-dimensional character expressions are seen as simply pointing to humans, so a two-dimensional character as a “symbolic” body will no longer be able to exist. How does the body of a two-dimensional character become a matter? And how is it excluded from becoming a body that matters? We need a theory that can deal with this issue.

Such a theory is the performative materialization theory of Judith Butler and Karen Barad. This is a theory that holds that “matter is always materialized” (Butler 1993: 9). It is also a theory that calls attention to the fact that “exclusions matter both to bodies that come to matter and those excluded from mattering” (Barad 2007: 57). This theory does not regard the distinction between the material and the semantic as self-evident but considers that the two are dynamically entangled. Furthermore, in this position, it is argued that Kantian thing-in-itself does not exist(Barad 2007) and that the Lacanian Real does not exist in itself but is established as a constitutive exterior (Butler 1993).

Barad’s theory is more general than Butler’s, as it covers all materials that are not limited to constitution of human bodies. However, because of this, Barad omits details about human mental processes. It cannot capture the texture of exclusion in the human thought process or how exclusion is experienced psychologically. When considering the issue of exclusion in human society, it is useful to view psychoanalytic phenomena performatively (in Butler’s terms).

In particular, when thinking about the queerness brought about by two-dimensional existence, the process of constructing “the uncanny” and “the un-uncanny” is important. The uncanny corresponds to “a situation in which the Real, meaningful meaninglessness, suddenly looms over the horizon of meaning (imaginary and symbolic)” (Chiba 2018: 27). In Butler’s terms, it is positioned as something to be foreclosed. On the other hand, “the un-uncanny” is a word coined by Chiba that corresponds to “meaningless meaninglessness.” It refers to “the nature of the body itself that causes finitude” as “the outside of the correlation between the familiar and the uncanny” (Chiba 2018: 28). Rather than being openly disliked as something uncanny, it can be said to be something that is passed over without any consideration. All of these point to the “outside” of meaning and society, but it is important to note that things placed outside are not necessarily things that are openly hated.

If we consider the exclusion of “the uncanny” and “the un-uncanny” as a dynamic process, we can say the following: On the one hand, the desire for mimetic empathy directed toward two-dimensional characters is rendered uncanny by those who adhere to human-oriented sexualism as something that has nothing to do with (hetero)sexuality or reproduction. On the other hand, in the human-oriented sexualist world, two-dimensional expressions are stripped of their materiality and unique historicity, reduced to mere representations of humans, and sometimes become un-uncanny. This simultaneously relegates the recipient’s desire for the character to the outside of what is socially meaningful, and under human-oriented sexualism, which domesticates characters into meaningful human representations, the material effects of being two-dimensional are placed outside the realm of meaning and cannot be put into words.

Shota Yamauchi, Tina sculpture, 2022 / Photo by Ryo Yagara

Implications for issues of gender and sexuality surrounding technological artifacts

What is important in this case is the trigger for differences in mimesis. As Willerslev points out, ” nothing is left to imitate when the difference between the copy and the original is totally gone” (Wilerslev 2007: 12). Differences are essential for mimesis to become mimesis.

And it was none other than Butler who emphasized the significance of activities considered imitative. Butler’s critique of gender essentialism questions the systems and customs that ” certain kinds of gendered expressions were found to be false or derivative, and others, true and original” (Butler 1999: viii). As part of raising this issue, in response to criticisms that see butch/femme and drag as reproductions of gender norms and heterosexuality and criticisms that see gay men’s practice of appropriating femininity as usurpation of femininity, Butler has developed a counterargument (Butler 1999). Butler’s argument is that imitating normative heterosexuality means that it is not a matter of completely copying and reproducing the norm.

Butler’s theory criticizes ” false assumption (…) that all straight sex is phallic and that all phallic sex is straight” (Preciado 2018: 62). Continuing this, Paul B. Preciado harshly criticizes the idea of equating dildos with phalluses and penises. The dildo is not a copy of the penis but a substitute that ” retroactively produces the original penis” (Preciado 2018: 67). And “The dildo diverts sex from its “authentic” origin because it is unconnected to the organ it supposedly imitates” (Preciado 2018: 68). A dildo is something that can lead to misdelivery into an act different from the “original” heterosexual intercourse.

The debate over the two dimensional can also be seen as an extension of Butler and Preciado. Two-dimensional female characters, in a sense, separate symbolic gender stereotypes from real, flesh-and-blood women, thereby creating a sexuality that is different from human-oriented sexuality. This kind of phenomenon is nothing but “dynamic misdelivery = subversion due to the object being animated based on the stereotype of femininity becoming separated from women, becoming independent, and becoming an entity different from women.” (Matsuura 2022: 68). This misdelivery challenges the idea that the source of femininity lies in human women. It also undermines the assumption that two-dimensional beautiful girls and human women are both the “same” female. Furthermore, it deconstructs the assumed self-evidence of (especially heterosexual male) sexual desire towards human women.

In the context of feminism, sexual representations of two-dimensional female characters that reproduce the heterosexual desires of male recipients are often discussed. However, from a feminist perspective, theories surrounding the sources of femininity and masculinity become important when considering two-dimensional male characters. For example, people who like “oresama” (pompous) male characters do not desire real-life men who have dominant pompous attitudes, nor do they affirm such masculinity. The same misdelivery as with the female characters occurs here as well. However, if we view the ontological difference between two and three dimensions as meaningless, we will be mistaken, as if these people prefer dominant men in real life. And considering that more women than men love “oresama” characters, ignoring the difference between two-dimensional and three-dimensional can reinforce the prejudice that these women desire to be dominated by men.

Given the above, butch/femme, drag, dildos, and two-dimensional characters should not be seen as, in and of themselves, reproducing normative gender and sexuality norms. Rather, what should be critically examined is the question of how the misdelivery and subversion caused by these things can be erased.

For example, Preciado refers to the assumption that phallic representations inevitably reproduce patriarchy as “negative sexology,” a play on negative theology (Preciado 2018: 70). However, an idea based on negativity assumes the existence of phallus-centricity through the denial of the phallus and ignores the materiality of the dildo, which is not recovered by the phallus.

The issue of neglecting materiality also pervades transphobic debates. Transphobic discourses are based on a “hierarchical order of materiality” that views cisgender bodies as “more material” and “legitimate” and views transgender bodies as “fake” (Fujitaka 2023: 34-35). Cisgendercentrism or cisgendersim tend to downplay the materiality and historicity of bodies that do not conform to these norms.

And the same can be said about the practice of assigning gender to artifacts. It is true that in our society there are situations in which artifacts can be said to have gender, and in a sense, it seems that we are assigning gender to artifacts (Saijo 2019). However, in reality, it is implicitly assumed that cases where gender is assigned to the human body are the original state of gender. The gender that is (or appears to be) assigned to artifacts may be seen as merely a representation of “human gender” and therefore less legitimate. In this context, I think the effect of gender being materialized in a way different from the human body is being neglected. If this is the case, humano-genderism is an idea that considers human gender to be fundamental while treating gender exemplified by non-human beings as “less material” and “mere representations.”

In this paper, I examined the material aspects of two-dimensional characters and the mimetic empathy that is the process of animating them, which are the factors that make two-dimensional characters a different type of being from humans. The establishment of a two-dimensional character is an ontological change in the sense that the list of “what exists” is revised. Ontological change also transforms human perception and desire in the sense that it creates a desire for a different type of being than humans, and therein lies an opportunity to subvert the normative way of gender and sexuality.

However, the possibility of such transformation is excluded by human-oriented sexualism. This erasure is nothing more than downplaying historicity and materiality and foregoing the possibility of change. This issue cannot be avoided when thinking about the gender of sex robots and AI. Rather than simply discussing the ethical pros and cons of technology and artifacts, we must carefully consider the issues surrounding the environment and the social norms surrounding technology and artifacts.*7

Shota Yamauchi, Tina sculpture, 2022

[Notes]

*1

For an overview of fictosexual research, see Matsuura (2023).

*2

In this regard, Jean-Marie Schaeffer explains the distinction between lies and creation as a pragmatic one (Schaeffer 2010).

*3

The author’s doctoral thesis (scheduled for submission in 2023) examines in detail the issue of how two-dimensional characters are generated, including consideration of “mimesis of the mind” and “mimetic empathy.”

*4

The techno-animism theory is the idea that because Japan has a traditional animist culture, Japanese people tend to view technological artifacts such as robots and AI as personal beings. Kureha (2021) carefully discusses the fallacies of techno-animism theory.

*5

See Matsuura (2023) for the relationship between such subversion and heteronormativity and gender norms.

*6

On the other hand, even if vegetarian food is no longer just a substitute for meat and fish, we may wonder if there was ever a need to imitate meat and fish in the first place and why we would go out of our way to imitate meat and fish. However, the act of imitating meat and fish was not intentionally chosen in a situation where you could choose anything. It was the result of a situation where a meat-eating culture already existed. It is necessary to distinguish between the problem of historical path dependence, the problem of ahistorical nature, and the problem of ethical value judgment.

*7

Regarding issues of gender and sexuality surrounding AI and robots, please also refer to Issue #01 on this site, “Inheritance of Memory, Plurality of Futures,” and especially the section “AI and Gender Representation.”

[References]

●Kayu Adachi: “Characters as Human Representations and Characters as Fan Contexts:The Dual Nature of Characters Created by the Social Activities of Consumer Groups”, Edited by Daisuke Nagata and Shintaro Matsunaga “Sociology of Anime: Cultural Industry Theory of Anime Fans and Anime Creators” Nakanishiya Publishing, 2020, pp.204-220

●Hiroki Azuma “Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals”, University of Minnesota Press, 2009

●Nobuyuki Izumi “Simulation of the Heart of Love: Expression of Characters Related to Same/Opposite Sex” Bijutsu Techo vol. 66(1016), 2014, pp.143-147

●Housei Iwashita “The Expressive Mechanism of Shōjo manga: An Open History of Manga Expression and ‘Osamu Tezuka'” NTT Publishing, 2013

●Makoto Kureha “Japanese and Robots: Criticism of Techno-Animism Theory,” Contemporary and Applied Philosophy Vol. 13,2021, pp.62-82

●Reina Saijo ” Towards Making Sense of Gender of Artifact” Memories of Institute of Humanities, Human and Social Sciences, Ritsumeikan University, Vol. 120,2019, pp.199-216

●Masaya Chiba “Meaningless Meaninglessness” Kawade Shobo, 2018

●Kazuki Fujitaka “Unearthing the Story: The materiality of Trans and a Narrative that Resists its Erasure” Natsuno Kikuchi, Yuri Horie,Yuriko Iino (editors) “Opening Queer Studies 3: Health/Illness, Disability, and the Body”, Koyo Shobo, 2023, pp.22-45

●Yuu Matsuura “Bishōjo as Metaphors: Gender Trouble by Animating Misdelivery,” Gendai Shiso (Special Feature = Metaverse) Vol.50(11), 2022, pp.63-75

●Yuu Matsuura “The Politics of Gender and Sexuality from a Fictosexual Perspective“, the lecture materials for the public lecture, 2023

●Karen Barad “Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics And the Entanglement of Matter And Meaning”, Duke University Press 2007

●Judith Butler “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity”, Routledge 1999

●Judith Butler Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”, Routledge 1993

●Paul B. Preciado “Countersexual Manifesto” Columbia University Press, 2018

●Jean-Marie Schaeffer “Pourquoi la fiction?”, SEUIL 1999 (Why Fiction?, University of Nebraska Press 2010)

●Rane Willerslev “Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs”, University of California Press 2007

●Kifumi Liao “Fictosexual Manifesto Their Position, Political Possibility, and Critical Resistance” 2023 (Accessed on 12/3/2023)

English version “Fictosexual Manifesto: Its Position, Political Possibilities, and Critical Resistance” (Accessed on 12/3/2023)

●Motschenbacher, Heiko. 2014. “Focusing on Normativity in Language and Sexuality Studies: Insights from Conversations on Objectophilia.” Critical Discourse Studies 11(1): 49–70.

Yuu Matsuura

Born in Fukuoka in 1996. Currently enrolled in the doctoral program at Kyushu University Graduate School of Human-Environment Studies. Specializes in sociology and queer studies. Co-authored “Feminist Phenomenology: Toward a Place Where Experiences Resonate” (Nakanishiya Publishing, 2023). Major articles include “Phenomenological Sociology of Erasure: On Marginalization that Accompanies Untypification,” Sociology Review, Vol. 74, No. 1, and “Asexual/Aromantic Multiple Orientations: Audience as Nonsexuality in Bloom into You,” Gendai Shiso 9/2021 issue, etc.