攻殻機動隊 M.M.A. - Messed Mesh Ambitions_

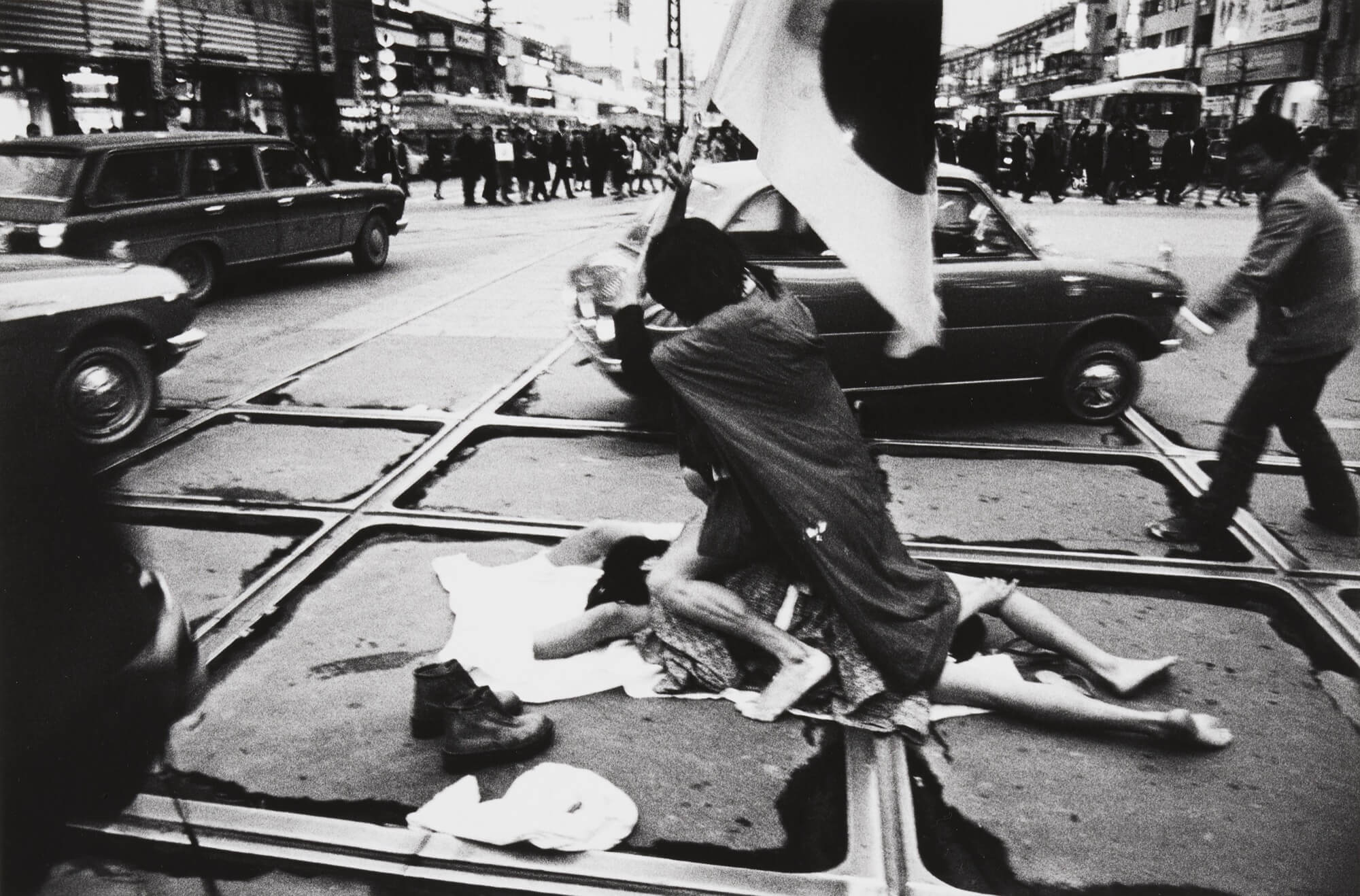

平田実「天神交差点の街頭ハプニング 集団蜘蛛と集団“へ”」、 1970年

©HM Archive / Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film

Libertin of the Void—The Extralegal Spaces of the City and the Body

[Credits]Text_Kyoko Ozawa

Images_Minoru Hirata

This is not the soliloquy of a genius ghost hacker who exuded his fearlessness when he was cornered at the end of an intense cyber battle with Major Motoko Kusanagi.──Rather, it is the opening sentence of the timeless classic novel “The Face of Another,” written by novelist Kobo Abe and later made into a film by Hiroshi Teshigahara.

Folds── Kyoko Ozawa, an art historian whose main areas of expertise are cities and architecture, is also known for her theories on “handsome men” and “visual kei,” but seems to have always focused on “folds.” Ozawa’s journey through the “folds of the far labyrinth” of “Ghost in the Shell” leads to cities that appear in the work, such as Newport City and Chinatown in the Etorofu Special Economic Development Zone, and the extralegal gaps lurking within the technologically closely connected “post-human” body; it is an external void, a “frontier folded into the interior.”

The brief libertinage is generated by “the frontier within,” which is also the title of Kobo Abe’s monumental essay. This is intertwined with the inherent outlaw nature of technology and causes various accidents in the world of “Ghost in the Shell.” After encountering trouble, the story turns into an outlaw without remorse.

This article can be described as a record of a speculative stroll in which I wandered, armed with a burnt-out map, exploring the “frontiers” that the story has yet to reach.

[Contents]

A void within the city or a frontier folded into the interior

Ruins are also associated with the “aesthetics of the sublime” in the West. It was in the 1980s that images of “ruins,” which are different in nature from the burnt-out fields and atomic bomb blast fields that were the original landscapes of the post-World War II era, began to overflow into the field of popular culture in Japan. When I think of ruins, I immediately think of Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira,” a post-apocalyptic landscape created by a final nuclear war. However, what creates a void in the city is that the derelict sites that have appeared in cities and industrial areas are a result of rapid industrial structural changes and urban redevelopment. (For example, the waste collection areas depicted by Keizo Hino, the abandoned factories that form the background of Tokyo Grand Guignol’s plays and Haruko Mikami’s installations, and the movies “Robinson’s Garden” and “Noisy Requiem,” depicting abandoned hospitals and ruined buildings where people with nowhere to belong are floating around the city gather, or the genealogy of ruin photographs by Shozo Maruta and Takashi Miyamoto)*1.

The “Ghost in the Shell” series is also located in this lineage of urban “voids” and “frontiers folded into the interior.”

The members of Public Security Section 9 in “Ghost in the Shell” belong to the system of state power as enforcers of the law. However, they meet with the boundaries of that system and end up extending beyond it, becoming entities that lurk in the gaps. In the first volume of the manga by Masamune Shirow, the Section Chief, Lieutenant Colonel Daisuke Aramaki, says that the purpose of creating Public Security Section 9 is to “identify and eliminate the sources of crime.” Public Security Section 9 is a group of law enforcers that truly belong to the national government, but unlike the police and military, who are bound by rules and discipline on all sides and are generally portrayed as incompetent mobs in the story, they are in a truly outlaw-like position. To carry out their mission, they are often placed in the void of a city connected to a computer network or in a remote place between the interior and exterior of the city.

In the “Ghost in the Shell” series, the image of Major Motoko Kusanagi jumping off a skyscraper and disappearing into the cracks while activating optical camouflage appears repeatedly. This is also a metaphor for the fact that the place of activity of Public Security Section 9 is the void in the newly established artificial city after the nuclear war. The Major slides through the voids between modern office buildings and futuristic skyscrapers. What appears as an equivalent “void” is the remains of urban development and the half-ruined old city as a space that grows naturally in the void of the city.

Director Mamoru Oshii’s animations “Ghost in the Shell” (hereinafter referred to as “G.I.S.”) and “Innocence” strongly expressed the visual image of a ruined place as a void in the city.

Newport City, the setting for “G.I.S.,” has an old town that is a “folded-in frontier” inside a modern or futuristic skyscraper district. Here, you’ll find an obscene market, a group of multi-tenant buildings that are collapsing and being expanded at the same time, alleys between them, drains full of floating garbage, brightly colored signboards with Chinese and English characters mixed together, and even buildings that are still in the middle of construction that are in ruins. Such sequences are interspersed throughout the work, with the downtown area lined with buildings with rusty iron everywhere (sometimes it’s the scene of a gunfight, and sometimes it’s just an establishing shot). The yellowing air of the photochemical smog that pervades the old town and the overall obscene atmosphere further accentuate the contrast with the inorganic, characterless, almost symbolic buildings. As the director himself has repeatedly stated*2, this old city is based on a location carefully chosen while scouting in Hong Kong at the time but is depicted as an imaginary city with no real references. Furthermore, in the final scene, a ruined Western-style mansion (obviously a reference to the Crystal Palace at the London World’s Fair) in a submerged and abandoned area of the old town is set as the stage for a fierce confrontation between the Major and the Puppet Master.

The Chinatown of “Innocence,” which moves the setting from Newport City to the Etorofu Special Economic Development Zone, is even more magnificent and fantastical. Locus-Solus is a chimera-like building that Oshii named “Chinese Gothic,” which is a fusion of Chinese tradition, a Gothic style reminiscent of the Milan Cathedral, and a vision of a skyscraper (in that sense, it resembles Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s fantasy architecture) and overwhelms the viewer. But this is by no means a cathedral as a center of religious authority nor a skyscraper as a flourishing center of economic activity. The Locus-Solus company has become a den of criminal organizations that have taken advantage of the ambiguity of the national government and is run by multinational corporations and their offspring, and a lawless zone that even the military cannot touch. They were in the middle of a huge group of stupas.

The inherent characteristics of video media, such as sequences of motion, time, and movement within space that are made possible by these things, and the unique characteristics of video media and the calculated, often-switching variety of camera work further accentuate the characteristics of this “place”*3.

Needless to say, the Chinatown-like image of the city is a reference to the half-ruined Asian neighborhood left in the middle of the near-future Los Angeles with towering skyscrapers that appears in the movie “Blade Runner.” Particularly in the United States, the system, technology, and norms symbolized by the overtly futuristic skyscrapers contain within them an unfamiliar and, at the same time, unaccommodating residue that is alienated from time to time. The Asian neighborhood in “Blade Runner” is represented as one who is separated by time and is systematically another, a place that is mixed and indeterminate, endowed with multiple otherness in the sense that it is also culturally, ethnically, and racially othered. In the ensuing cyberpunk boom, the motif of an obscene and dirty Asian neighborhood left behind in a futuristic skyscraper district was expressed as a “void” outside or at the border of the law, places that should be called an “internal frontier.” “G.I.S.” and “Innocence” can also be linked to this lineage of Asian neighborhoods (although there are various intentionally embedded differences) in terms of urban representation.

From the lineage of representations of Asian neighborhoods connected to “Blade Runner,” we can find Orientalism in the “West,” or “techno-Orientalism,” as well as its intentional reference in Japan (Reflective Self-Orientalism). While advocating for concepts like “postmodernism,” the region that transitioned from the era of imperial powers through the Western nations during the Cold War (essentially the Western sphere) still drags along Western modernity. Themes such as “colonies” and “internal frontiers” (typically seen in immigrant neighborhoods) in this region, or the duality of Japan as both the “other within” in terms of Western modernity and internalizing Western modern mentality while holding a colonial position towards other Asian countries, are embedded in the representation of the city as the “Oriental” other frequently seen in the lineage of cyberpunk.

Newport City in “G.I.S.” is the temporary capital of Japan that was established on an artificial island in the sea as a transitional stage in the plan to move the capital to Fukuoka after the destruction of Tokyo in a nuclear war. Deep within the completely artificially constructed new capital, a place with almost no history or memory, lies a kind of remote or exotic place called Chinatown. On the other hand, Etorofu, the setting for “Innocence,” is originally Ainu land if we consider the actual historical circumstances, but it is an “internal frontier,” or a “void” in the system of national sovereignty, where it is part of Japan’s territory but is still under effective control by other countries. The Etorofu Special Economic Development Zone in the story has become a place where cutting-edge technology clusters due to government deregulation. In this way, although Newport City and Etorofu Special Economic Development Zone have different origins and characteristics, they are both cities with a short history that were politically constructed in places that are peripheral to the nation (on the sea or in the Northern Territories), and they are covered by high-rise buildings that appear to have been built relatively recently. In each of these works, an old Chinatown appears as a remnant left behind by progressive time or continues to resist the development of its surroundings.

Compared to the representation of the Asian neighborhood in “Blade Runner,” the Japanese language is excluded from the Asian neighborhoods in “G.I.S.” and “Innocence.” Japan was naturally included in America’s image of the “other” as both exotic and unsettling. In contrast, in the case of the two works produced in Japan, to express the “inner other,” it was probably necessary to remove the country from the image of “Asia.”

The Asian neighborhood in “Blade Runner” is probably modeled after the real Chinatown in Los Angeles, but there are signage advertisements and lines in Japanese mixed in with Chinese, and there is also a scene where a group of Krishna worshipers go on a parade. It is depicted as a city that is a mixture of Asian (or “Asian” from an American perspective) elements. It is clearly depicted from an Orientalist perspective that is behind the West, that time for progress has stood still, and that is why it is mysterious and suspicious, and I have a feeling that it will soon disappear as we move towards a technologically advanced future. On the other hand, the old foreign neighborhoods that suddenly appear in emerging temporary capitals and special economic zones that appear in “G.I.S.” and “Innocence” do not necessarily mean that the districts that existed in ancient times were left behind by the surrounding development. Rather, they exist as a naturally occurring “foreign substance” of unknown origin. These Asian neighborhoods are a place that has not been subject to any unified planning or management, and while parts of it are constantly collapsing, at the same time, bricolage-like additions are being piled up in a chaotic manner. It is a place like a living organism that has its own organic system, such as the coral that appears in Batou’s dialogue in “Innocence.”

Compared to the two anime works directed by Oshii, the manga version by Masamune Shirow, the first volume of which was published in 1991, generally compresses both the story and visual information. There are not many scenes that visually “draw in” the locations themselves. The difference in the nature of the media, manga and anime, may also have an effect. However, the settings where the crimes and accidents that Public Safety Section 9 must investigate occur include garbage dumps, old arcade shopping streets that retain the atmosphere of the post-World War II black market, and abandoned small factories and warehouses situated in narrow, unkempt back alleys. In contrast to Oshii, who introduces blatant exoticism into such settings, Shirow’s manga presents signs and other elements written primarily in Japanese.

In contrast to the narrow voids within the city where bugs and hacks occur, there is a contrast between the outside of the city, the deck of a ship floating on the wide ocean, and even underwater, which is often depicted using large sesame seeds. It would be an open space. In this underwater and above-water setting, the Major’s body is shown in close-up, and the creation of that body (the prosthetic body) and immersion in sexual sensations are depicted. The open space of the ocean is by no means outside the network but rather is covered in a mesh of connections through individual “cyber brains” and appears to be the literal embodiment of network metaphors (for example, expressions such as “net surfing”).

The aforementioned images of ruins or urban “voids” created by the fictional imagination of the 1980s also reflect the reality of technological self-runaway and failure. Examples include current events such as the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident, the Space Shuttle Challenger launch accident, and the Japan Airlines jumbo jet crash. Accidents related to technology appear as individual accidents that come from outside humans, pretending to be coincidences, but they are inevitably inherent in the technology itself. In the 1980s, Paul Virilio called this an “integral accident” or “Ur-accident”*4. To put it bluntly, technology is also a kind of outlaw. Although it appears to bring about a society perfectly controlled by humans, it sometimes eats away at it from within or destroys it from the outside. In “Ghost in the Shell,” accidents such as the void of technology or the other held inside often occur in Chinatown and ruins, which serve as voids or “folded in frontiers.”

The world of “Ghost in the Shell” is set in the near future, where “cyberbrains” and their high-speed networks, “prosthetic bodies,” “micromachines,” and “IR systems” for monitoring and management have become widespread. The void of hackers and bugs trapped within management and control, or the outside of the system, overlaps with the space where extralegal activities take place in the city.

平田実「博多・天神の街頭ハプニング 集団蜘蛛」、1970年 ©HM Archive / Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film

Posthuman as a liminal and marginal place of the body

The “Ghost in the Shell” series features posthuman beings in the most obvious sense, such as cyborgs, robots, androids, and even animals and children (in their infancy) in the animated series. However, apart from these motifs, there is also marginality and liminality at the boundaries of the concept of humanity in “Ghost in the Shell.” This can also be called an outlaw trait.

In the “Ghost in the Shell” series, the posthuman nature of the connection between technology and the body is combined with extremely positive and utilitarian effects such as enhancement, communication efficiency, and acceleration. It is also connected to the destruction of the body, the disconnection and malfunction of networks, and the act of libertinage (the absolute freedom as an extralegal, dissolute and unrestrained behavior), which one steps into without realizing it. For example, in Shirow’s manga version of “Ghost in the Shell,” there is a scene in which the Major connects the bodies of two women, shares their sexual pleasure via cyberbrain, and they amplify each other’s pleasure using micromachines. Here, for example, as in the “libertin” thought of the Marquis de Sade, through sexual licentiousness that goes beyond existing norms, it seems that both institutions and the self itself are destroyed and annihilated; perhaps we can see an opportunity for radical freedom.

“Ghost in the Shell” is set in a near future where individual bodies, cities, and cyberspace are combined. Individual brains are connected to a network and become a “cyberbrain.” Although it is not a constant connection and can be selected at the will of an entity that can be called a “unique component,” instant “cyber communication” is possible. Now that this is the situation, the network as a whole is considered to form something like a huge collective consciousness, and the traditional and simple premise of the division of “human beings as individuals” is in jeopardy.

In addition to the connection and fusion of humans and machines, in “Ghost in the Shell,” humans and cities are also connected, embedded together, and networked. In “Innocence,” there is a scene where the city is compared to a giant external storage device, and Batou views the skyscrapers below the Etorofu Special Economic Development Zone—”a group of gigantic stupas” with a Chinese Gothic design—and sees the city as a huge external memory device. In a conversation with Togusa, Batou says, “If the essence of life is information transmitted through genes, then society and culture are also nothing but vast memory systems, and cities are huge external storage devices.”

In the world of “Ghost in the Shell,” where the post-human situation seems to have reached its peak, there are still human personalities called “ghosts” in the story, as opposed to “individual existence.” Intermediate organizations that are collections of individuals, such as the “family,” the fictional organization of the state, and internal organizations that are subordinate to the state, such as the “police,” “military,” and “public security,” are still alive and well. At the beginning of the first volume of the manga version, the year 2029 is set as follows: “In the near future, corporate networks reach out to the stars, and electrons and light flow throughout the universe. The advance of computerization, however, has not yet wiped out nations and ethnic groups.” In 2030, the setting of the TV anime series “Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex,” “It is a time when, even if nets were to guide all consciousness that had been converted to photons and electrons toward coalescing, stand-alone individuals have not yet been converted into data to the extent that they can form unique components of a larger complex.”

Although individuals are connected to networks, they always have their own bodies. “Prosthetic body” technology can be incorporated into a part of the body to turn one into a cyborg, or it can be used as a “fully prosthetic body” so that one “enters” a completely artificial human body, and even the brain can be transformed into a cyborg. Humans without a prosthetic body, humans with a partially or fully prosthetic body, and robots are virtually indistinguishable from each other (and robots can also be equipped with AI or a “dubbed ghost,” and those with a humanoid appearance are called androids). This “inability to tell the difference” also causes various accidents and crimes in the story.

However, there are moments when the simple dividing line between the “unique components” and the “whole network” disappears.” In “G.I.S.,” the Major, who temporarily leaves her prosthetic body, fuses with the Puppet Master and becomes a being who is absorbed into a network and whose outline as an individual disappears. Even so, although her “brain case” is retained within the woman-shaped prosthetic body, the ghost fuses with the network through the Puppet Master. When talking about the Major fused with the Puppet Master, the classical dichotomy or division of “the soul and the body as its container,” as well as the simple boundaries of self and other, which once defined the existence of humans, and the definition of the individual as being “no further divisible,” are no longer useful. If we push this into the schema of classic philosophical questions such as “personal identity” or the “Ship of Theseus,” we have no choice but to maintain the concepts of “personality” and “a whole that is separate and autonomous as individuals,” and what is happening here becomes considerably trivialized. The fusion of the Major and the Puppet Master is itself an example of speculation about the emergence of life in a sea of information. At the same time, it is also the moment of the arrival of radical freedom, which will be thrown completely outside existing laws and collapse the contours and foundations of existence*5. Similar opportunities can be found in the use of Kim’s brain case to back up Batou’s ghost in “Innocence,” and in the manga version’s promiscuous sharing of sexual pleasure through the connection and resonance of the body and senses.

In other words, this posthuman situation erases the traditional boundaries between humans and other things, not only on a technological level but also in terms of legal status. This libertin and extralegal radical freedom, is expressed by the members of Public Security Section 9, who are basically “law enforcers” even though they are outlaws. Especially with the Major, it comes in the process of “law enforcement” (in this respect, it is reminiscent of Sade’s Libertinage, which goes beyond existing laws and moral norms by thoroughly enforcing independently established rules). This freedom is likely to be temporary and fluid, and there is a strong possibility that it will be regained through the development of future technology and the development of legal norms.

平田実「退散! 集団蜘蛛」、1970年 ©HM Archive / Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film

Epilogue

Something like this extralegal “void” or “a frontier folded into the interior” is covered by a cyber network, but it is still incomplete. There is a phrase that is repeated in the series: “Even though technology has advanced, the information age has not reached the point where the systems we take for granted are completely abolished.” In the world, it appears briefly and then dissipates. If we follow the story as a whole, it may be interpreted as a type of “restoration of order at the end” (perhaps this is due to the inevitable need for a work to be united and become autonomous). However, the outlaw-like “void” in the “Ghost in the Shell” series is a prerequisite for our thinking within the stand-alone complex, like the interconnection of individual works in the series, and there is something embedded in it that escapes the concepts separated by existing languages. That is to say, going beyond the relationship of “a single center and its derivatives” to “the original work and its adaptation,” they are autonomous and sometimes contradictory, but are loosely connected to each other and continue to generate a single “worldview.” It may seem like a minute detail, but it is actually the decisive core.

[Notes]

*1

The factors that influenced the popularity of ruin-like representations in the 1980s include the cyberpunk trend, with the 1982 release of “Blade Runner” as the banner, and the so-called “dead tech” style of photography in Europe and America (mainly Western countries at the time). An example of the latter is a photo book of abandoned rocket bases by Argentinian photographer Anna Barrado (featuring photos taken from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, published in Japan as “Anna Barrado” by Atelier Peyotl Label in 1989). There was also West German Manfred Hamm’s “Dead Tech: A Guide to the Archaeology of Tomorrow” (published in 1981 in West Germany and 1982 in the United States) or French journalist Sophie Ristelhueber’s “Beirut,” which depicts the landscape devastated by the Lebanese Civil War (published in 1984, Haruko Mikami is also said to have been influenced).

*2

Mamoru Oshii “Innocence Creation Note: Travel between Doll, Architecture, Body + Talks,” Tokuma Shoten Publishing, 2004. Stefan Riekels, “Anime Architecture: Imagined Worlds and Endless Megacities” (translated by Yuko Wada), Graphic-Sha Publishing, 2021, etc.

*3

It would be impossible to describe this sequential visual experience in words, so please watch each video streaming on this website (https://theghostintheshell.jp/streaming).

*4

Conversation between Paul Virilio and Akira Asada, from the November 4, 1988 issue of “Asahi Journal.” Akira Asada, “Beyond the End of History,” Chuko Bunko, reprinted in 1999.

*5

However, this freedom is also incomplete, and the Major still needs unity as a unique component called a “prosthetic body,” or a dividing line drawn between him and others. At any rate, the plan of the Puppet Master within the network is to obtain the rather conventional and simple destinies of the human body, such as “death” and “procreation.”

Kyoko Ozawa

Professor, Faculty of Humanities, Wayo Women’s University. She completed her studies at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and holds a Ph.D. Her field of expertise is representational cultural theory, with a particular focus on the relationship between the body and space. She has authored “ANATOMIA URBIUM: Separatio, Decapitatio, Corruptio Aedeficiorum / Corporium” (Arina Shobo, 2011) and “L’écriture de la ville utopique: la pensée architecturale de Claude-Nicola Ledoux” (Hosei University Press, 2017). She has co-authored “Critical Words: Fashion Studies” (Film Art Publishing, 2022) and “Straub Huillet: Toward Absolute Cinema” (Shinwasha, 2018), and has published essays such as “A Journey to Another World Through Architecture.” (“Gendai Shiso” 51 (13), 2023), etc.