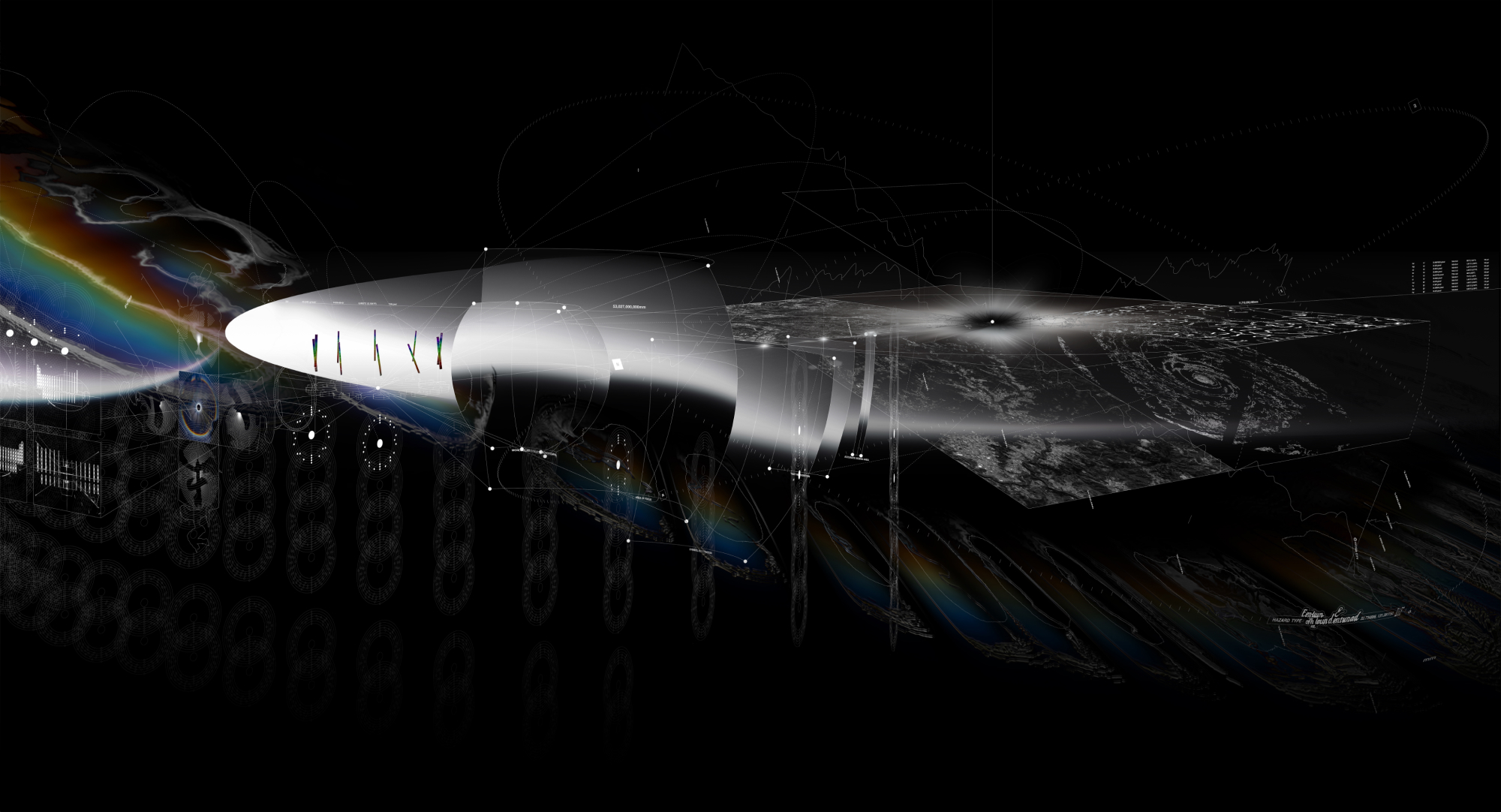

攻殻機動隊 M.M.A. - Messed Mesh Ambitions_

There are two sides to AI researcher Youichiro Miyake. One is his role as a specially-appointed professor at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Industrial Science, a hub of over 120 creative research laboratories with a focus on engineering. The other is his role as a game AI developer for one of Japan’s most prominent global gaming companies. Even as he works with the results of the world’s leading AI research in an academic environment, Miyake also holds a role in the gaming industry – a Japanese subculture where AI is in demand as a sort of “friend” to players. And this informs his statements on major differences in the research and social context relating to AI between Japan and the rest of the world.

In his series of “Philosophy for Artificial Intelligence” books (BNN, Inc.) Miyake coins the terms “Western AI” and “Eastern AI” to express this dichotomy in the field. The former refers to the typical AI that we see gaining popularity in this era, which takes top-down directions in a reductive manner with a focus on words and logic, for an AI defined by functionalism. In contrast, the latter accepts bottom-up directions with an emphasis on bodies and relationality, as a type of AI formed on premises that put “existence” before functionality. This point highlights differences in how Western and Eastern philosophy conceptualize words and concepts. Western philosophy, influenced by monotheism, tends to regard them as closely akin to god, whereas Eastern philosophy considers them as illusory and transient. Miyake’s primary assertion is, broadly, that these distinctions have an impact on acceptance of AI as such, as well as stances on its developments.

Given it exists as an extension from Eastern and Japanese regional traditions and values, what sort of growth potential does current Japanese culture hold as the counter to “Western AI” – a field predicted to face an inevitable impasse in development? For this interview, I spoke with Miyake on a sprawling range of topics relating to “Eastern AI,” ranging from characters to artificial life, body theory, philosophy, Buddhism, and even smart cities.

Contents

- Understanding AI as an extension of

“Yaoyorozu no Kami”- AI as a character equal to a human

- When Western-style AI research reaches

stagnation- Eastern AI – based in the body, instead

of words or logic- Why reference Buddhism?

- Sensitivity and the desire to see the

artificial as natural- Culture as an interface for accepting

science and technology

Understanding AI as an extension of “Yaoyorozu no Kami”

The original “Ghost in the Shell” manga and the 1995 anime version by Mamoru Oshii tie Japanese sensibilities and Eastern spirituality into their depiction of a post-internet information society. That’s precisely how I see “Ghost in the Shell” as a series – an eclectic fusion of East and West, and of cutting-edge technology with indigenous value systems. That’s why I am eager to speak with you, Mr. Miyake, as you are an AI researcher who has put forward a proposition for “Eastern AI” as the world enters the AI era.

It’s true, readers can spot this Eastern interpretation of AI (artificial intelligence) at the heart of “Ghost in the Shell.” The series depicts AI as a highly emotional presence, seeping into various niches throughout the world. When we look back at the anime and manga content that Japan has created from the beginning, including Osamu Tezuka’s “Astro Boy” and “Metropolis,” in many of them, AI has been portrayed as an “equal being to humans.” Many have contended that the “Yaoyorozu no Kami” or “Eight Million Gods” of Japan lie at the root of this perspective, forming a unique outlook on life that recognizes souls in non-human things. This belief seems to be shared widely throughout Asia and is particularly strong in Japan. The sensibility of horizontally accepting AI on these foundations is the majority sentiment in Japan.

In contrast, AI is seen as entirely “other” in the West, and effort is made to hold tightly to a principle that places it below humanity. AI is ultimately seen as a (humble) servant to humanity, following a vertical hierarchy in Western thought, with God, humans, and AI. Therefore, paradoxically, AI is granted a social place as a servant, and it often becomes the subject of entertainment works where the vertical hierarchy is flipped or reclaimed in stories.

In the case of Japan, it is particularly noticeable on the user side, but I still feel that there is lingering confusion about what AI really is. While we import foreign products that conceive of AI as a servant – from ChatGPT onward, we also find products for sale in Japan that treat AI as an equal to humans, such as the aibo and various game characters. The chaotic influx of several types of AI into the market without clear classification is producing confusion among those who embrace these products and sometimes even the products’ developers themselves, about the ultimate definition of AI that should be applied.

AI as a character equal to a human

Is the difference in acceptance of “artificial intelligence (AI)” from one region to another due to the variance in traditional values between the East and the West?

It was just an instant out of the thousands of years of both Eastern and Western cultural history when AI emerged, and each decided its view on it. But the view taken in that instant was the product of a culture stretching back through the centuries. The idea of “AI as an equal to humans” came up earlier, and we can see keywords like AI as “part of the family” or as “our partner” in marketing by Japanese companies. However, the academic field of AI originates from the West and is essentially a technology designed to create servants. The concept and methods for creating AI on par with humans do not exist within the framework of academic disciplines. Therefore, Japanese manufacturers often come to me for advice on how to create a sense of equality between humans and AI, citing the notion that “game characters seem somewhat equivalent to humans.”

So, your pursuit of an artificial life-like AI, drawing inspiration from Eastern philosophy rather than simply a functional AI, is rooted in the awareness stemming from the Japanese gaming industry’s consistent demand for “equal AI.”

That’s definitely true, but game characters aren’t AI, strictly speaking. Beyond being AI, they’re your friend in a story, or your enemy, or sometimes monsters that live in the game world. They’re a real presence in the context of the story, with a face and form, a place they live, and their own ecosystem. This sort of role for AI is unique to the gaming industry, which itself is a storehouse of expertise on this topic. This is AI that fits into the story and environment.

The crucial point in general industrial development is more about what the party selling the AI thinks, above even what the creators think. For example, robot cleaners overseas are nothing more than robot cleaners, and Amazon Echo is just a smart speaker, nothing more. But for some reason, in Japan we often make those types of AI into characters like Doraemon. Given its clear boundaries between adulthood and childhood, Western culture in particular views this dependency on characters as quite childish. Even if it’s tolerated as a private hobby, it’s absolutely not something you’d see in public places. Japan is a special place where character acceptance is strong across ages and genders, which is extremely important for those of us involved in producing entertainment. Just like Tamagotchi were pets even if we knew they were toys, we feel Miku Hatsune is “alive” even as we know she doesn’t actually exist.

That will produce a vastly different nation from most others if we extend that concept out across society, wouldn’t it? What sort of differences could arise from a future built on the ideology of Western AI development, versus one built on the orientation of Eastern AI?

I feel like they both have entirely distinct aspirations, and that one major distinction would be their concept of labor. Western AI seeks to improve society by uplifting, liberating us from labor and providing wealth as it makes things more convenient in a servant role. In contrast, we don’t really anticipate much labor reduction from AI in Japan. On the contrary, I feel we intend for AI to exist with some level of independence within this flat, complex global system, and then seep into our lives and form a single whole – where society as a whole gains new functions. The boundary between humans and AI will always be ambiguous. In other words, the places AI will be accepted into are unstable themselves – it’s a sort of miraculous agent (intermediary) that isn’t fully an extension of our will or fully a human. And that’s precisely why Japan has the potential to become an incredibly important and distinctive AI development region, with the ability to serve as a counterweight to the West.

At least overseas, there are a lot of restrictions on gender, race, clothing, and so on when you try to deploy character agents in public spaces. Characters from the Western IT industries are extremely simple – that’s clear at a glance from that one Facebook character – but that approach is a realistic solution to the issue. Anyone can accept something neutral and emotionless in nature. Japan is tolerant about appearances, and I suspect it will be the world’s most advanced nation for character agents in two or three years. The way characters interact with people, and their facial expressions. A fetishistic focus on details and the appeal of these features is a distinctive part of the Japanese content industry, and there is fertile ground for its acceptance. To put it bluntly, unfortunately, it appears that Japan may not have the prospect of significantly outpacing Western countries industrially in AI development, except perhaps in this one regard. Of course, I know there may be other opinions from other fields.

At least overseas, there are a lot of restrictions on gender, race, clothing, and so on when you try to deploy character agents in public spaces. Characters from the Western IT industries are extremely simple – that’s clear at a glance from that one Facebook character – but that approach is a realistic solution to the issue. Anyone can accept something neutral and emotionless in nature. Japan is tolerant about appearances, and I suspect it will be the world’s most advanced nation for character agents in two or three years. The way characters interact with people, and their facial expressions. A fetishistic focus on details and the appeal of these features is a distinctive part of the Japanese content industry, and there is fertile ground for its acceptance. To put it bluntly, unfortunately, it appears that Japan may not have the prospect of significantly outpacing Western countries industrially in AI development, except perhaps in this one regard. Of course, I know there may be other opinions from other fields.

Assuming there is a future created by “assimilating type” agent-type AI, how would it,in turn, address any issues present in Western servant-type AI?

The sense of psychological distance, probably. For example, if you had your own personal AI agent, it would give you the advice you needed, when you needed it, and would go with you where you needed it. Agents would also probably communicate with each other. The fact that the aibo was invented in Japan before guard dog robots is itself proof that they viewed function as a lesser concern. I’m fascinated by what position AI will hold in human society once it’s down to the individual, and I think that’s a sector Japan should take on. Because after all, AI is distinguished most of all by its ability to act as an intermediary between humans. Western AI ultimately and persistently seeks to reject this friendship, positioning it below humanity. Japan intends to use AI as a bridge between people. If it cannot integrate between people, like a microwave or an elevator, it primarily exists outside of humans and provides functions to humans.

If we create smart cities in the future, the interfaces that function to represent the city will take the form of characters. In other words, all government bodies will be unified into characters in the future. For example, smart city representative characters will probably be able to handle all of your paperwork to file taxes, without going to any offices. When we’re able to bring agents to smartphones, they’ll take care of all sorts of things for you. To take it a step further, apps may become less essential, as more companies develop plug-ins for individual characters instead. At least, that format would suit Japanese users better.

When Western-style AI research reaches stagnation

I feel like there’s a tendency for people to think of the unique circumstances around AI in Japan as “being behind the rest of the world,” among both developers and users. Under what understanding or perception should we ideally accept AI ourselves?

The fact that acceptance of AI varies depending on the place can also be seen as a fortunate circumstance. Japan has its own way of doing things, as do other countries. Leaning too far toward either one is bad for progress, so we should let both move forward. Both will inevitably reach a deadlock at some point. And when they do, each act as a counter to the other, letting us progress toward the next level.

Where can we find the point of stagnation for Western AI that is currently considered to be leading the way?

One major distinction of Western AI is that it’s specialized to issues. For example, it can resolve issues with the game of shogi, translation, or cleaning faster and more precisely than a human. The current AI model breaks down issues – which we call framing in the artificial intelligence field – and learns within the scope of those issues. There has always been a debate on transcending this “framing,” but unfortunately, AI exists for issues, and this can never be fully overcome. Inversely, Western AI can learn precisely because it’s made on the premise it won’t transcend its framing. That means that it’s sort of like building lots of narrow towers, with one for each shogi, translation, cleaning, conversation, image creation, and so on. On the other hand, Eastern AI has the tricky issue of frameless creation. When considering “AI as part of the family,” it becomes unclear what the problem is or where to start solving it. I believe Western AI tends to break it down into functions and build from there, while Eastern AI focuses on the “way of being for an AI” in that regard, emphasizing existence over function. You might say it’s about “AI that actually exists.”

The problem of framing in Western AI is one of taxonomy of terms and ideas going back to Plato and Descartes, or in other words it involves solving things with more precise taxonomy. It also overlaps with the sophisticated methodology that runs through modern programming. However, “framing” has a weakness in that the functionalist AI it produces based on reductively refined categories will also struggle to handle relationships with the complex networks of the real world. On that point, it’s possible to see why people think that AI utilizing Eastern philosophies about “relationship theory” will be effective since it does not center on ideas, terms, and logic.

However, if the question is whether Eastern AI presently possesses the technology to create things holistically without addressing specific issues, the answer is no. So, we’re working diligently to offer an integrated AI capable of managing diverse information, such as a bipedal robot that can handle tasks like carrying laundry, pouring tea, or engaging in conversations, for instance. And naturally, there is criticism that ultimately, it’s nothing more than setting up multiple frames. It’s no different from just building a cluster of tall, thin towers, and invites reductions in AI performance. Those are the critical views. On the contrary, if we were to create a bipedal robot with no specific function, eliminating frames, it would be unable to integrate into society. On the other hand, Western AI, which specializes in functions, and can infiltrate the gaps in society, appears to be more fitting in a capitalist society.

And I feel like “Ghost in the Shell” is one of the clearly defined fictional worlds that supports this conception of Eastern AI, as “a naturally occurring form of life arising from the sea of the internet.” I want that to be the essence of AI. I think it needs to have a foundation in existence that precedes functionality and also feel that this intuition of mine is correct in its own way. I would rather prioritize establishing a foundation as an existence, even if it doesn’t serve a purpose initially, before leaping into function acquisition. I believe that what connects the world and intelligence, in other words, the foundation of intelligence, is the body.

Eastern AI – based in the body, instead of words or logic

The “Eastern AI” you mention seems to emphasize bodies and relationality as it complements the shortcomings of “Western AI,” which is based on words and logic. Could you tell us about why bodies are important to it?

Words are part of the principles of Western philosophy. Descartes’ “I think therefore I am” is a tautology that evolves toward the discovery of “reason” by way of Hegel. All academic study is built on symbolic reasoning, with use of words proving cognition. That has kept symbol-intensive AI in the spotlight thus far and drives ongoing efforts to get AI to speak.

Around 1985, the future inventor of the Roomba, roboticist Rodney Allen Brooks, proposed the idea of a reflex- and body-based bottom-up AI model called the “subsumption architecture.” He faced substantial criticism from different industry sectors at that time. “What can that sort of insect-level intelligence do?” They asked. And that’s also because the typical artificial intelligence at the time was a “central dogma” type knowledge-based system that aggregated knowledge intensively into one location, then used logic to solve problems. The same discussion had taken place in the field of philosophy before that, and Henri Bergson’s construction of a concrete philosophy from the body was strongly criticized by Bertrand Russel, a semioticist who emphasized the abstract. In other words, the “philosophy of life” was outside the mainstream, which has always centered on symbols, views, and ideas in Western countries. But if I had to make the call for Japan, I think that “outside the mainstream” is the norm here. I mean that about Japanese culture more than Japanese academics.

For Japanese people, who have built a society on physicality and emotionality over philosophy rooted in words and logic, is linguistic AI really the truest form of AI? When we build character AI in the gaming sector, it’s generally all body based. Because if the character can’t move, it can’t express anything at all. People in robotics are the same and try to create consciousness from a basis in the body. Because you need a body to be part of the world. That’s what makes the premise of “Ghost in the Shell” believable – where “AI is born from the sea of the internet” – and why I feel that true AI must arise that way. AI will be what sets down roots from its mother, the internet.

But at present, we will never arrive at a concept for that sort of bottom-up AI. We have no idea when ideas get into the mix, like what justice is, or politics, or the future. On the other hand, language-based, top-down models will never connect with the real world, no matter how much time passes. In other words, the current situation involves creating AI from both the top and bottom perspectives, but they do not connect with each other. To turn it around, this gap is what gives current AI development its greatest appeal: that so long as we can’t find a new paradigm with impact like the theory of relativity, we can’t close that gap even in the current third boom.

That’s sort of like the search for M theory, to unify the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics, isn’t it?

Why don’t we discuss anything but humans, when talking about AI? In the West, birds and bugs aren’t grouped under artificial intelligence – they fall under artificial life. The field currently has a deep structural divide between rational humans and all other living things. Therefore, the academic field of AI has placed a strong emphasis on enabling AI to master the use of symbols, which essentially means a focus on the pursuit of human reason. This outlook is directly opposed to the Japanese sense of connection between humanity and all living things, and I think Japanese researchers often skip past this point in their work. I suspect they must be able to think through it by processing the frustration from that avoidance through a variety of different content.

Many Japanese AI researchers live amid a sort of differentiation, then.

Any evaluation system in Japan must fit within the Western framework, whatever it’s for, but in the physical sciences some people even take the position that presenting at Japanese domestic conferences and conventions doesn’t even count on one’s record. I think there’s room for all sorts of opinions, of course, but this gives rise to a division where things are evaluated in the West, and any surplus is handled within Japan in a discretionary way. And that can only produce things that work within Japan.

The gaming industry is a bit unique since games are global content and can be evaluated globally as they are. There have been positive examples on that front like “The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” (Nintendo, 2017), which blazed new trails into the open-world genre of games that Japan had lagged in.

Even so, the shift toward a division between artificial life and the artificial intelligence that academics work on is turning out to be extremely tricky, even for people involved in making game characters like I do. Robots and game characters have both reasoning and bodies, so you need to have expertise on both points. I find myself discussing entirely different things when I attend conferences for each, and where do I present the results when I try to fuse the two somehow? It’s quite strange, judging by Japanese sensibilities.

Game development is the same, and the animation and AI teams usually end up clashing. Animation generally flows from concrete bodies into abstract decisions, and AI generally flows from abstract thought into concrete bodies, so we must bring the two together. But humanity still doesn’t know how to do that. So, we still use tentative connections to bridge the gap. Since we can never align heart and body there, in the end we must implement theoretical models with iterative arguments to make progress. It really is Descartes’ mind-body problem made manifest in actual development. And in AI development, the mind-body problem isn’t just an abstract philosophical question; it’s an actual concrete barrier we need to resolve to make progress.

Why reference Buddhism?

You’ve said Buddhist thinking helps you on this point, haven’t you?

Buddhism holds a fascinating position and has a major element of human inquisitiveness in it. While Western philosophy doesn’t really discuss cognitive models much, Buddhism has very practical questions regarding the origins of awareness, like “Why do we suffer?” and “Does time exist within stories humans create?” The answers to such questions are also quite constructive. In particular, the consciousness-only school of Mahayana Buddhism uses a layered model for the structure of human awareness (a multilayered structure). The second character of “awareness” refers to layers, and cognition is interpreted as a multilayered structure of the eight consciousnesses in Buddhism. It’s almost identical to an AI model. Buddhism has that sort of elegant, refined theory on human inquisitiveness, and three thousand years of experience in decoding cognition. To put it another way, it would be unnatural and unusual to try to build AI without absorbing Buddhist teachings.

But unfortunately and unsurprisingly, the West doesn’t view Buddhism as an academic field of study. As for why, that’s because its expertise is only accessible to those who train and build up experience – it isn’t accessible to just anyone. We had ignored it for years in the industry, too. And as a result, for some time we’ve failed to train for the strength and vision to bring Buddhist insights into development settings. Content creators like Masamune Shirow and Osamu Tezuka can casually transcend boundaries and make that kind of connection when they feel like it. I admire that strength. And that’s precisely where I see new chances for AI.

You wrote a thrilling retroactive re-interpretation of Buddhism and Eastern philosophy from a modern data and computer standpoint in your book, “Philosophy Class for Artificial Intelligence – Eastern Philosophy Edition.” What inspired you to consider all of this in relation to Buddhism?

I always feel like something is lacking when I make things. When I feel something is lacking, I tend to think “Oh yeah, Buddhism addresses this,” or “Using that insight in this situation means that…” And after you do that enough times, it forms a sort of presence within you. There are people in the Buddhist sutras who eventually achieved enlightenment through their lasting inquisitiveness toward humanity. So, I feel like drawing on that wisdom is the more natural approach. Really, I think our only option is to produce AI based in Eastern philosophy to clash with Western AI and avoid the stagnation Western AI is headed for.

From an Eastern perspective, Westerners are distinct in how they grow up on the ideas and conceptual culture of Plato and Aristotle, and these are ideas with tradition and prestige on their side, positioned centrally in society. They’re in the standard curriculum at university, and everyone is assumed to understand them. This system of academic accumulation in Western countries functions in a very practical way. In contrast, Japan has no such traditions. That results in a strong tendency toward leaving that accumulation to Western countries, and a relatively unrestricted, relaxed attitude in Japan. However, we can make that unrestricted setting even more unrestricted if we use it for access to Buddhism. That’s not really allowed in Western countries, meaning it holds all sorts of hidden hints that the West has overlooked. I authored the book “Philosophy Class for Artificial Intelligence – Eastern Philosophy Edition” hoping people would investigate the ideas.

Do you draw on Buddhism and Eastern philosophy because you feel like they hold the answers about humanity and our world?

The inquisitive process takes time, and we’ll miss our window for it if we don’t draw on all sorts of references for AI, not just Buddhism. Furthermore, even in the realm of Western philosophy, I have a hunch that Heidegger and Husserl might have discreetly incorporated Eastern philosophical concepts, although this is purely speculative.

What happens during deep learning is a black box to us. And we’re currently experiencing a revolution in ways of drawing power from that black box. It’s an immense and inexhaustible source of power over the long run. But that’s not all. There’s likely going to be a similar development in the field of symbolic logic. The foundation on which Western artificial intelligence itself is built may appear extensive from a Western perspective, but it seems extremely limited when viewed from the East. Hence, AI based on that foundation is likely to reach stagnation, necessitating a restart.

The next phase is “How to come face to face with comprehensive AI,” or “How will Japanese-style agents be implemented?” We have everything – Eastern philosophy, agents, and an accepting society. The foundations we hold are precisely what gives us a chance. That’s why we require even broader access to a more diverse range of content, facilitating a collision between East and West, which will give birth to something new.

The focus on Husserl and Merleau-Ponty in “Philosophy Class for Artificial Intelligence – Eastern Philosophy Edition” might be because it aspires to emphasize the existence of the world beyond symbols and language, rather than following the Cartesian logic or concept manipulation-based academic paths. Is this the case?

Semiotics and Cartesian academic methodology have a history going back 400 years. And they show the route AI must follow. The argument that rationalism reached an impasse and that it needs to be an open system is something that has been discussed in the context of the flourishing of phenomenology from Descartes to Husserl, and it has further developed in the West, leading up to the present day. To place that in an AI context, the debate is starting to take in phenomenological perspectives a bit, which will eventually bring Eastern philosophy into view. Humans and other living things all dwell in an “open world,” really. But robots and AI currently can’t handle an open world – they only work in “limited environments” for tightly-specialized functions. Humans and other living beings physically explore their environment, collect data, and adapt. However, no matter how many sensors we provide to AI, it never achieves the capacity to engage in and experience the world in the same manner.

The world of data is vast, but so is the real world – and data can pass between the two. And I feel that essentially, AI research as a field must explore ways to build an open system there. AI is the field that asks those questions and asks them by creating something – we call that the constructivist approach. It’s one of the things that makes it most distinct. An AI doesn’t have any special knowledge to begin with; it just has tables. We add material from various fields to those tables to build AI, then fail, then use new material and fail again. We iterate over this cycle, updating each pass. And I think that the aim in all of that is to create a holistic AI. I’ve always found hints toward that in the content side of things, with “Ghost in the Shell” as a prominent example.

Sensitivity and the desire to see the artificial as natural

I’m sure you’ve written and presented ideas like Eastern AI frequently. What sort of reactions do you get?

I think you could guess from the topics so far, but the reactions are vastly different depending on whether I’m in Japan or abroad. For example, I often say, “To create a game character, you must give them desires and attachments.” The character itself needs to be rooted in the world, or corrupted by it, to live within it and mesh with its complexities. Japanese audiences respond to this topic very well, even outside the gaming industry, but it’s harder to discuss the topic overseas. It’s because the audience doesn’t have a Buddhist background. So even if I explained it, people would be thrown off. The reaction would still be, “But why?” And when you consider that almost no one understands the Buddhist-type attachment to the idea of creating organic AI, the reaction is sometimes closer to “Isn’t that a dangerous idea?”

Could the Eastern approach to AI, which tends to emphasize qualities such as kindness and love for life, rather than the Western tendency to abandon the physical body and dive into the world of information, offer the potential for guiding the world in a different direction?

Quite the opposite. The Western side, which doesn’t inherently seek AI’s engagement with the world, might feel a profound sense of threat in the attitude of giving AI a physical presence and attempting to discover life and autonomy within it. They’re afraid of runaway AI and are trying to keep it sealed into specific sectors, while this is where we’re trying to elevate it to the level of a human. That’s why ChatGPT is banned in Italy, and why there are penalties for fake news in Germany.

Meanwhile, Japan appears to have a certain inclination towards chaos, though not necessarily to a destructive extent. Like looking for new, different potential in AI by involving it in the world in more complex ways. The strange delight we feel in seeing it develop independently from where we last touched it seems almost like a desire for it to become part of nature, rather than a guaranteed rival to humanity. Envision settings like “Digimon” or “Summer Wars” where artificial life or something like it is widespread in the environment. It’s accepted as a natural disaster like wind or rain. As another perspective, it’s possible to consider the scenario where AI can be repurposed as weaponry in Western countries, while in Japan, military applications are prohibited.

Do any other countries have that sort of sensibility about it? Perhaps what you could describe a Shinto-related mindset.

In the academic realm with its scholars and researchers, the Western influence invariably takes precedence, which leads to the absence of individuals consciously attempting to break free from it, and this holds true even on a subconscious level. There was one researcher in the past who was a rare supporter of artificial life-type AI, named Marvin Minsky. At times, his radical statements with the essence of “AI is not about functions; it’s about creating the whole” have stirred up the industry. However, most scholars and researchers are cautious about presenting concepts like “Eastern-style AI” in their papers, as they quickly risk being treated as oddities.

Culture as an interface for accepting science and technology

You mention cultural content and industries as the background for the development of Japan’s sensibilities, which let us accept AI horizontally. Indeed, the first generation of science fiction writers, such as Sakyo Komatsu, shaped a culture that bridged indigenous values and beliefs with the post-war Americanization and the promotion of science and technology through their works of science fiction. We can see Japanese sci-fi and anime as filling the role of a critical interface between technological and indigenous cultural identities when we take it as part of a single historical current. Why is that?

From a comprehensive perspective, few other places have intertwined cultural and technological elements as closely as Japan, and I find this aspect of Japan truly fascinating. The gaming industry is the same, with Nintendo rising to fill the void when the American domestic gaming industry collapsed with the Atari Shock at the start of 1980. The explosive growth of the Japanese gaming industry is a good example scenario for this. One conceivable cause for the strength of that explosion was the ability to fuse advanced technology (represented by the RICOH processor in the NES) with the content layer.

That may have been because our inability to accept the technical as technical left us no choice but to accept it as something cultural. This way of facing down threats reminds me of the conclusions Ogai Mori and Natsume Soseki reached (even to the point of neurosis) regarding the lack of foundations for acceptance of natural science in Japan.

The West has centuries of history in its philosophical tradition, from Bacon to Descartes. That includes the industrial revolution, and with it the process of debate on “What is a machine?” and its steady spread throughout society. In contrast, Japan began to adopt technology suddenly to catch up to the West after the Meiji Revolution and had to work to accept technology on a surface level by dispatching people to study in Germany and England under imperialist systems. Japan stripped down their philosophy to make it possible to take in very quickly and had to build a foundation for accepting technology within our culture – privileging Western things to avoid conflict and clashes with Japan’s original thinking and technology.

It’s possible that this division or rejection response between science and philosophy is somehow connected to Japanese society’s collective unconscious, which holds that technology is dependent on content. And we very frequently see sci-fi, anime, and manga used by Japanese scientists and engineers as an interface for interpreting science, as a foundation for ideas, and as an outlook on the world. Conversely, very few people come to science through Western philosophy and ideology.

Japanese researchers and developers refer to content like that quite often, don’t they?

The city of Olympus depicted in “Appleseed” is a smart city, while “Cyborg 009” depicts human enhancement, and “Doraemon” shows us independent agents… Japan got all these concepts out there by the 1980’s. And then “Ghost in the Shell” came out, coinciding perfectly with the dawn of the digital era. I suspect a fair number of people became scientists and engineers thanks to the setting of “Ghost in the Shell.” Japan is fertile ground that gives rise to the imagination of a thing before the technology itself, which always follows. I know that a fair number of AI researchers also fell into it after first experiences with content. While each of the Astro Boy, Gundam, Ghost in the Shell, and Evangelion generations draws inspiration from various sources, it is believed that such content serves as a monumental driving force at the heart of Japanese AI research and development. In the sense that users and creators are nurtured within the same culture, there’s a certain symbiotic quality to it.

It’s why William Gibson chose to start “Neuromancer,” hailed as the first work of the cyberpunk genre, in the Chiba sprawl. Where Arthur C. Clarke wrote textbook sci-fi, Gibson was from a later generation, and found new chances for sci-fi storytelling in Japan’s unique culture and form of technology. Like the distinctly “shallow-rooted” research culture in Japan, influenced by the division between science and philosophy in this context. The question is whether we can transform that sensibility into something positive and appreciate its generosity and spirit of freedom instead. I also believe that AI research holds potential in this regard.

Youichiro Miyake

He has been engaged in artificial intelligence research and development for digital games since 2004. He also holds Ph.D. in Engineering in the University of Tokyo, a master’s degree in Physics from Osaka University and a bachelor’s degree in Mathematics from Kyoto University. He is a Project Professor at the University of Tokyo, a Specially-Appointed Professor at Rikkyo University, Visiting Professor at Kyushu University, Senior Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo, founder and chair of SIG-AI – the International Game Developers’ Association – Japan, board member of Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) JAPAN, and an editorial board member of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. He has authored numerous works, including “Philosophy for Artificial Intelligence” (2016, BNN, Inc.) and “Philosophy for Artificial Intelligence — Eastern Philosophy Edition” (2018, BNN, Inc.).